The real sin of $750 Bethpage Ryder Cup tickets isn’t the price

A ticket to a full day at the Ryder Cup at Bethpage Black will cost $749.51.

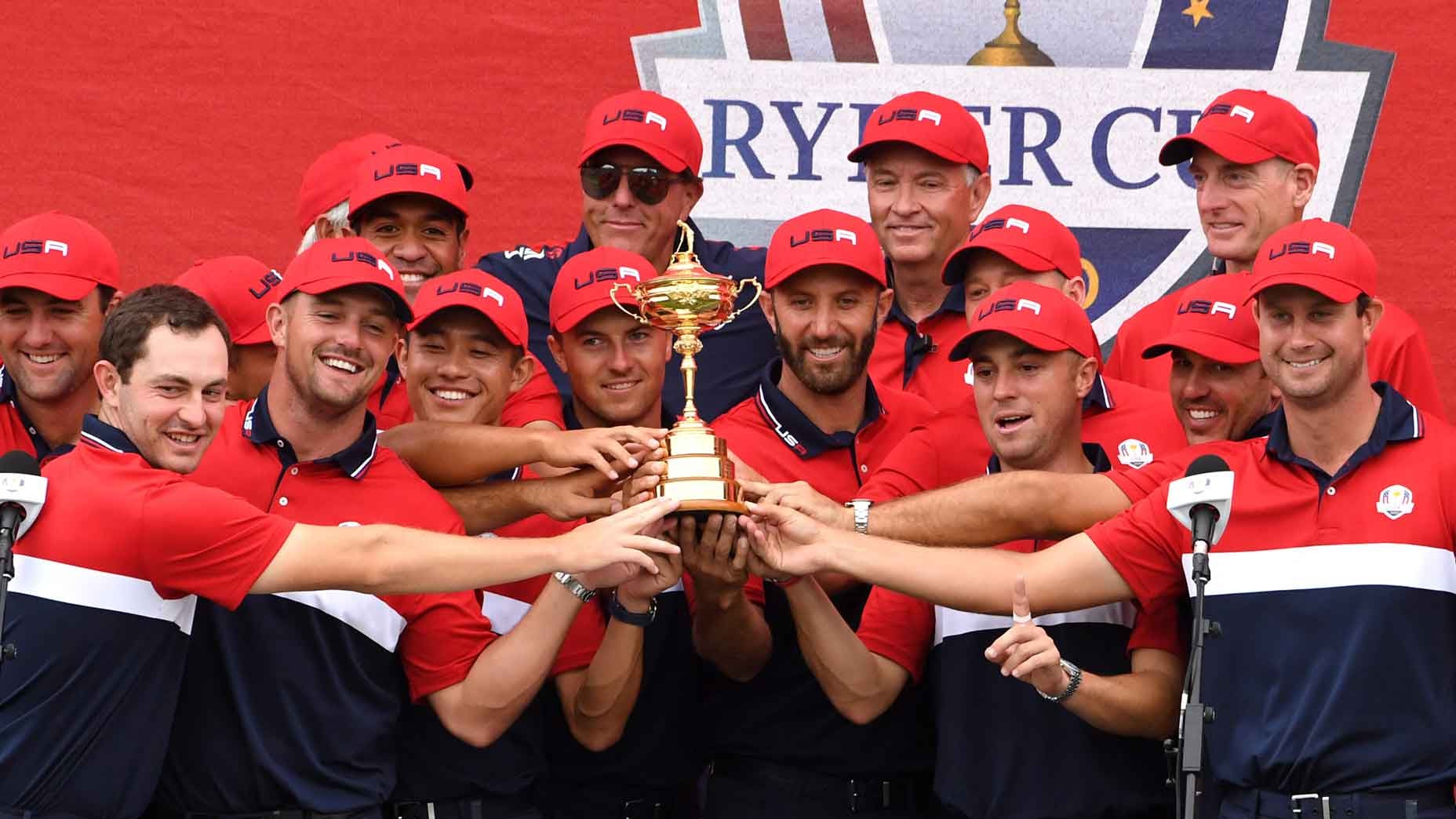

Getty Images

Bethpage Black’s history began, fittingly, with a bargain.

The year was 1933, and with the world encased in a Depression-era employment freeze, New York State commissioned a massive public park on Long Island to induce a thaw. To bolster the project’s public support, legendary power broker Robert Moses pushed to develop a series of municipal golf courses on the land, including a top-flight public course built explicitly to compete with Pine Valley. The idea was noble, but it required a skilled hand — someone who knew not just how to manipulate land into a golf course, but how to make a golf course have meaning.

Thankfully, A.W. Tillinghast was going broke. One of the eclectic fathers of golf course design, Tillinghast was an unlikely choice for a public works project. He’d spent the better part of the two decades preceding 1933 developing some of the greatest golf courses in the world, but then the Depression arrived and the demand for his work disappeared. Tillinghast was burning through cash fast, and when the Parks Department offered him a job consulting the Bethpage design process for $50 a day — a pittance for Tillinghast, even in those days — he accepted without question.

The Black Course finally opened in 1936, and Tillinghast was quickly hailed as a hero (alongside course designer/superintendent Joseph Burbeck). The course was a revelation, and, for $2 on weekdays and $3 on weekends, it was perhaps the greatest bargain in public golf.

More or less, that is how things remained for the 88 years that followed opening day at Bethpage Black. The rates were tweaked over the years — now up to $70 for New York State residents, and double that for out-of-staters — but the value never wavered.

And neither did the people.

ALMOST A CENTURY LATER, the latest chapter in Bethpage Black’s history began with a cash grab.

On Monday morning, word leaked to the golf world: the 2025 Ryder Cup at Bethpage Black would be the most expensive iteration of the event ever staged — and perhaps the priciest golf event ever. At a staggering get-in price of $749.51 for each of the three competition days, the cost of a ticket to the Bethpage Ryder Cup would be almost seven times as expensive as a ticket to the PGA Championship at the same host site in 2019, and the equivalent price of 11 competitive rounds played on the Black Course during the high season. When the

The organizer for both events, the PGA of America, quickly defended the 581 percent price increase from 2019 — nearer to the presale price for a potential World Series game between the Mets and Yankees ($1,056) than any golf event — as the product of converging market forces. The new ticket prices, the organizers said, more accurately reflected the cost of hosting an event in the New York Metro area, the time spent on-site relative to other major sporting events, the access and proximity to star athletes granted by a ticket, and the cost that tickets might sell for on third-party resale markets. Organizers also noted that the Ryder Cup pricing helped fund best-in-class experiences for ticketholders, like a recent program offering fans unlimited food and soft drinks.

“We view ourselves as a Tier 1 event,” Ryder Cup director Bryan Harms told SiriusXM. “That’s on-par with a World Series or with an NBA Finals game 7.”

But organizers admitted the pricing decision wasn’t entirely driven by the “Invisible Hand” of economic demand. The PGA of America also had to protect its financial interests as a for-profit organization. With only one home Ryder Cup every four years — the PGA of America and DP World Tour split Ryder Cup hosting duties — 2025 represents a golden financial opportunity for the PGA of America. By jacking up prices and lopping off a piece of the third-party ticket revenue for themselves, the PGA of America could put on a better show while placing more money in the reserves for future PGA initiatives — a proverbial win-win.

“We took a lot of feedback,” Harms told GOLF.com. “We got to this point where we felt like, look, this is what we feel confident in.”

One would hope the feedback sought by the PGA of America extended beyond the literature of Adam Smith, because within the first five minutes the PGA might have learned about the dangers of the “Invisible Hand,” negative externalities, and the other word sometimes used to describe them.

Greed.

IT IS CHEAP TO CALL the PGA of America greedy for the Ryder Cup ticket prices, but not because it is untrue. It is cheap because the word greed has become an overused adjective for golf in the same way spinny is an overused adjective for chip. These days, golf and greed go together like an overcooked hamburger and an Aquafina at the PGA Championship — omnipresent and mildly nauseating.

To call the PGA of America greedy is to point out the obvious, and pointing out what is so eagerly and self-evidently true somehow undermines all of the other unsavory things that are less eagerly and less evidently (but no less obviously) true.

Unsavory truths like how we still don’t know what will happen to the extra $75-ish million in ticket revenue generated from raised ticket prices (a conservative estimate). Interestingly, the PGA of America has yet to pledge any of that money to Ryder Cup player compensation.

Players are famously not paid for playing in the event. Rather than a paycheck, the PGA of America gives a charitable donation to a cause of each player’s choice. One wonders what Stefan Schauffele, father to PGA Championship winner and multiple-time Ryder Cupper Xander, thinks about the PGA of America collecting an additional eight figures on the back of his son’s free labor and “love for country.” Could it sound similar to his suggestion from Rome in 2023 that players ought to “share in the profit”?

“Instead of being so damn intransparent about it, they should reveal the numbers,” Stefan Schauffele said then. “And then we should we should go to the table and talk.”

Or are we talking about other unsavory truths, like the PGA of America’s implication that the only golf audience worth catering to in the New York area is those who can afford to spend a few thousand dollars in a single afternoon? There is risk with this decision, and not only the kind that comes in bad PR. Has the PGA of America considered what it would do to the Ryder Cup’s reputation if Larry Luxury Box and his buddies decide not to paint their faces and wake up at 4:30 a.m. on Friday morning, leaving the famed 1st tee stand half-empty? Have they considered how such a high-paying clientele might respond to the minor imperfections of a temporary golf tournament, like a 30-minute bus ride from Jones Beach parking lots? And what will they say to golf fans when those fans realize their $750 ticket does not include alcohol sales?

Individual concerns aside, there are questions the PGA of America must answer for the broader public, too. Has the PGA considered how an overly corporatized, deeply sanitized environment at Bethpage might look to golf fans who have watched their sport besieged by those same forces to a bilic degree over the last five years? And speaking of turning away, has the PGA thought about what its decision will do to scores of casual sports fans in New York during one of golf’s rare weeks of broad sports appeal? The PGA of America is right to view the Ryder Cup as a Tier 1 event (or something close to it), but Tier 1 ticket prices aren’t the only component. There is an implied responsibility to provide a Tier 1 broadcast, Tier 1 security experience, Tier 1 traffic routing and Tier 1 merchandising line.

Ultimately, though, these unsavory truths are just mild annoyances next to the cardinal offense of these Ryder Cup ticket prices — an offense summarized so simply it almost sounds redundant: They’re doing this to Bethpage.

It feels trite to suggest that Bethpage exists on a plane above anything else in the golf world. Like most other golf courses, The Black is a business with financial aspirations, cold economic realities, real strengths and weaknesses. But Bethpage Black represents much more than a golf course, because it speaks to something much larger than golf.

Even today, the Black is an exercise in radical, almost overwhelming inclusion. Any New York State resident can walk the fairways at the Black course, so long as they have a set of clubs, a pair of legs and 70 bucks to their name. Comb the course on any afternoon and you will see this vision come to life — Fortune 500 executives and sheet metal workers; finance bros and golf pros; friends and strangers. Tee times are hard to find not because an invite is tricky or membership is small; they are a rarity because there are so many eager golfers and so few hours in the day. Bethpage doesn’t believe in equality, it is the embodiment of it — rich or poor, big or small, somebody or nobody; you can play.

A $750 Ryder Cup ticket fundamentally contradicts this idea. It tells us golf belongs to somebody instead of everybody. It suggests we come to grips with that reality, and don’t complain. It separates those who love golf from those who can afford it.

Bethpage has never been about haves and have-nots. It earned its favor precisely because it rejects golf’s less worldly ideals of elitism and exclusivity. To install these ideals for the Ryder Cup is not just an affront to all that Bethpage stands for — it’s a sign the PGA of America never understood it in the first place.

Thankfully, the PGA of America was at least right about one thing: The cost of Ryder Cup tickets is a once-in-a-lifetime deal.

For $749.51 per person, you can experience Bethpage Black like nobody has before — in body, but not in spirit.

You can reach the author at james.colgan@golf.com.

Related

5 Things I Never Play Golf Without: David Dusek

Our 11-handicap equipment writer always brings his favorite divot repair tool, a portable speaker and some high-tech gear to the course.As long as the weather i

Donald Trump’s golf course wrecked by pro-Palestine protesters

Pro-Palestinian protesters have vandalized parts of U.S. President Donald Trump's golf course in Scotland in response to his proposal for the reconstruction of

Man holding Palestinian flag scales London’s Big Ben hours after…

CNN — Emergency services were called to London’s Palace of Westminster on Saturday a

EPD: Drunk driver parked car on golf course

EVANSVILLE, Ind. (WFIE) - Evansville police say they arrested a man after finding him drunk in his car that was parked on a golf course.Officers say they were c