The most fulfilling jobs in America may not be the ones you expect

A priest, a lumberjack and an entrepreneur walk into a bar. Which one is happiest?

It’s definitely not the bartender – she’s doing one of the jobs least likely to give you satisfaction in life.

How in the world do we know that? Well, a while back, when we looked at the happiest jobs – shout-out to forestry – we considered how happy folks felt while at work. Outdoor jobs look awesome by that metric, dangerous as they often are in the long run, but readers kept reminding us that there’s more to a fulfilling job than how happy you are while doing it.

We didn’t have a stellar way to measure other feelings about work, but we kept our eye on an often-overlooked federal data provider: AmeriCorps. The independent agency, which CEO Michael D. Smith described to us as “bite-sized” but “punching well above our weight,” funds the Civic Engagement and Volunteering Supplement, part of the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey.

True data aficionados may remember the CEV as the source we used to find that Boston and Philadelphia are among the nation’s friendliest cities (yes, we were stunned, too). In 2021 and again in 2023, the researchers behind the CEV asked if you agree or disagree with these four statements:

• I am proud to be working for my employer.

• My main satisfaction in life comes from work.

• My workplace contributes to the community.

• I contribute to the community through my work.

The two years of surveys give us enough responses to start doing some serious analysis – or, in the grand tradition of this column, some less-than-serious analysis.

The questions may sound subjective compared with the usual Census Bureau fare, but they’re the next big step in a slow-building but snowballing academic effort to better measure the non-pecuniary benefits we get from our jobs. As the luckiest Americans worry less about their basic needs, more of us are seeking jobs with a moral or social mission.

“As traditional third places where Americans engage with their community are waning,” said Smith, the AmeriCorps CEO, “it’s great to see that workplaces are creating a space where employees can put their values into action.”

For better or worse, this shift has blurred the boundary between professional and civic life.

“There is this expectation or this desire for people to find meaning in the work that they’re doing and feeling like it contributes to some greater good,” AmeriCorps research and evaluation director Mary Morris-Hyde told us. Americans are more and more interested in working “for a place that gives them time and respects and encourages and wants them to be good citizens in their community.”

And – as your local newspaper reporter or AmeriCorps staffer could probably tell you – having a job that allows you to fight the good fight while on the clock may be worth forgoing a better paycheck elsewhere. But who gets to do these jobs?

The basic demographic outlines are easy to draw. As a rule, you feel better about your job as you get older. Presumably it’s some mix of people who love their work delaying retirement, people job-hopping until they find meaningful employment, and people learning to love whatever hand they’ve been dealt.

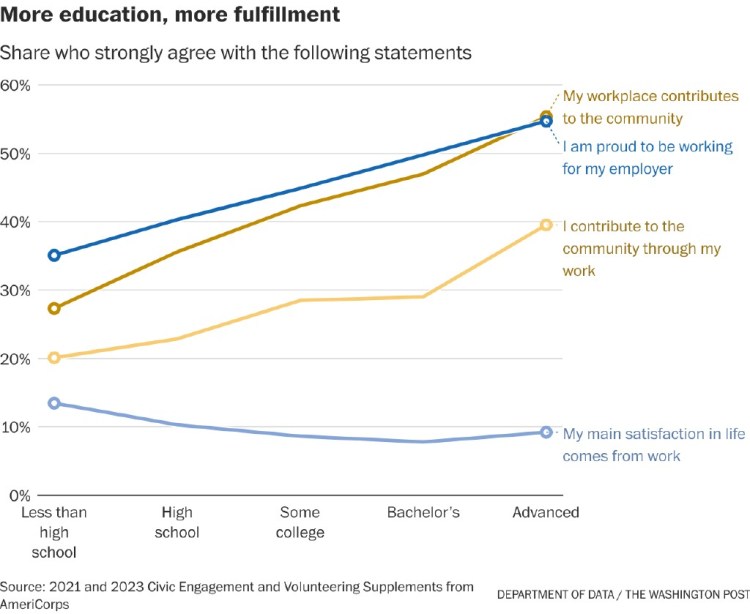

Most measures of satisfaction also rise with education, often quite sharply. Someone with a graduate degree is twice as likely as a high school dropout to strongly agree their workplace contributes to the community. There’s one exception: More-educated folks are actually a bit less likely to strongly agree that work is their main satisfaction in life.

But demographics aren’t the main event. As you probably guessed, much of our job satisfaction depends not on who we are, but on what job we’re doing. In that, we see a separation in the questions about personal satisfaction and the questions about contributing to the community.

The workers most likely to say they’re proud to be working for their employer and that they gain satisfaction from work are – surprise! – the self-employed. The self-employed who are incorporated – a group that often includes small-business owners – are almost twice as likely as private-sector, for-profit workers to strongly profess pride in their employer.

Government and nonprofit workers fall somewhere in the middle on those questions. But they rank at the very top on “My workplace contributes to the community” and “I contribute to the community through my work.” Local government workers, who include teachers, take the top spot for strong agreement on both, followed by nonprofit workers. Private-sector, for-profit workers once again lag behind.

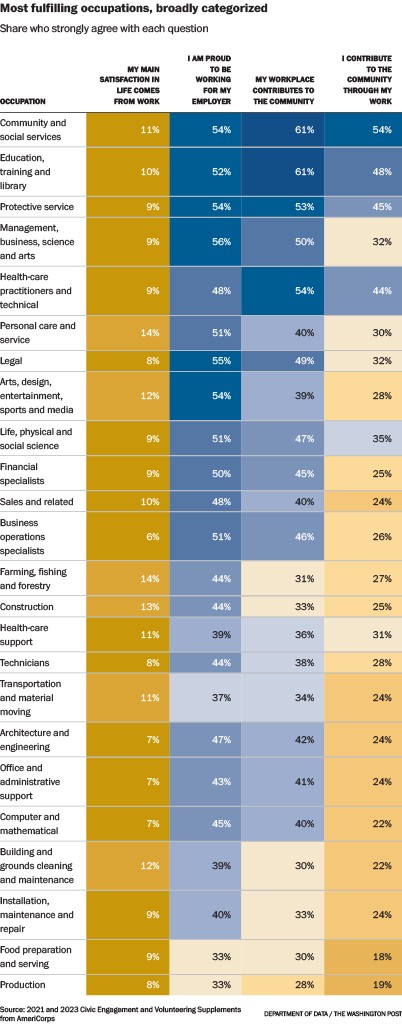

The jobs that do worse on these measures tend to be in manufacturing or other blue-collar production and extraction jobs, or at the lower-paid end of the service sector. Folks in food services (e.g., bartenders and food prep), janitorial roles and landscaping, and personal services (e.g., barbershops, laundry and hotels) all struggle to find greater meaning in their work. Though some better-paid service jobs also struggle by some measures – think sales, engineering or software development.

On the questions regarding pride in your employer and life satisfaction, we see managers and our old friends in agriculture and forestry take the top spots. But right behind them – and actually in the lead in the other question – lurks the real standout, a set of jobs we’d classify as “care and social services.”

That includes, most notably, religious workers. Looking a bit deeper at about 100 occupations for which we have detailed data, we see clergy were most likely to strongly agree on every question.

When we did our column on the happiest jobs, readers such as the Rev. Elizabeth Rees in Alexandria, Virginia, who left the legal profession to become an Episcopal priest, asked why we had ignored the spiritual angle. We didn’t have enough responses to isolate clergy in that particular dataset, but the clues were there. As Rees pointed out, Americans rank religious and spiritual activities as the happiest, most meaningful and least stressful things we do.

And if we look at places instead of activities, houses of worship top the rankings in all three measures. So we maybe should have seen the clergy coming.

To understand why religious workers would be so dang happy, we tracked down economist Olga Popova at the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies, part of a publicly funded web of German research powerhouses. From her perch in Regensburg on Bavaria’s Danube plain, Popova wrote the book – or more specifically the book chapter – on religion and happiness research.

She and other scholars have found a strong relationship between religion and well-being. And they’ve found that active participation in religion – beyond simple affiliation with a mosque or temple – increases the well-being boost. And nobody participates more actively in religion than the clergy!

Furthermore, Popova said, clergy may gain a greater sense of purpose through their deeper engagement with church doctrine. In particular, research shows religion better equips folks to handle some of life’s trials and tribulations.

“It’s plausible that clergy, through their constant work of helping others cope, develop a heightened ability to contextualize their own struggles,” she said. “By guiding parishioners through difficult times, clergy may acquire valuable skills and insights that buffer their own well-being.”

But of course, religious work may also attract the sort of people who prioritize living fulfilling lives.

“Individuals drawn to religious careers are more likely to possess certain personality traits, such as altruism or a strong sense of purpose, that are independently linked to well-being,” Popova told us.

To help untangle this web of causes, we called the Rev. Cheryl Lindsay, minister of worship and theology at the United Church of Christ. Among endless other responsibilities, Lindsay mentors and trains young pastors and has, since 2019, led a congregation in Wellington, Ohio.

As we ticked off the survey questions, each seemed to resonate more than the last: Of course, she’s proud of her employer, both God and the Deity’s servants on earth. And of course her work contributes to the community! For well over a century, the red-brick spires of her church have loomed over Main Street in Wellington, an old-growth hamlet of fewer than 5,000 people south of Oberlin where Lindsay provides food assistance and serves on community boards working on everything from overdose prevention to local theater.

“That is also one of the things that I truly love about being a pastor,” Lindsay said. “It’s a great fulfillment to be able to engage beyond Sunday morning, beyond Bible study, beyond the confines of our religion, to be in community with others outside the faith.”

Such work has exposed her to a breadth of human experience far beyond what she saw in her previous life as a banker, she said, and given her skills to apply to her own life: “In effect, you minister to yourself out of the reservoir that you build.”

Lindsay noted that, to be sure, her job can be stressful, isolating and demanding. Work-life balance often eludes her. A typical pastor is running a small business and putting on weekly events even as they help parishioners navigate the highest peaks and deepest valleys of their lives.

“You don’t get to divorce yourself from the messiness of life. I’ve been in hospital rooms, visiting a member of the church. If they have a health crisis – I’m there. I’ve got calls in the middle of the night because a parishioner lost a child,” she said. “Those moments bring a heaviness.”

At the same time, Lindsay said, she has been “the first one to visit new parents when their baby is born. I’ve baptized babies and adults who have decided to join the church. I’ve officiated weddings. I’ve been invited to graduation parties.”

“The fulfillment, I think, is really sharing life with one another, but also … drawing people deeper and deeper into their faith – which also can fortify your own.”

Related

A top recruiter says sports marketing roles are hot right…

Jobs are opening up in the sports industry as teams expand and money flows into the industry.Excel Search &

Public employees and the private job market: Where will fired…

Fired federal workers are looking at what their futures hold. One question that's come up: Can they find similar salaries and benefits in the private sector?

Mortgage and refinance rates today, March 8, 2025: Rates fall…

After two days of increases, mortgage rates are back down again today. According to Zillow, the average 30-year fixed rate has decreased by four basis points t

U.S. economy adds jobs as federal layoffs and rising unemployment…

Julia Coronado: I think it's too early to say that the U.S. is heading to a recession. Certainly, we have seen the U.S. just continue t