Meta-analysis of the red advantage in combat sports – Scientific Reports

Criteria for inclusion of Summer Olympic Games

We included the Olympic Games from 1996 to 2020 (N = 7 sports events) as 1996 was the first year in which the clothing colour of athletes was reported in the Results Book published quadrennially by the Organizing Committee. The sports outcomes were obtained from the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG; 1996), the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC; 2000), the Athens 2004 Organizing Committee (ATHOC), the Beijing Olympic Development Association (BODA; 2008), the London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games (LOCOG; 2008), the Rio de Janeiro Organizing Committee (ROOC; 2016), and the Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic Games (TOCOG; 2020).

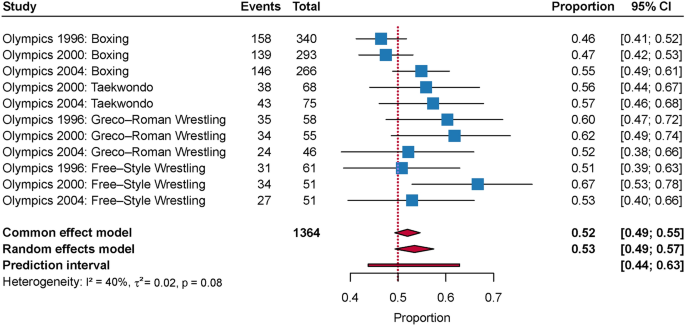

In line with Hill and Barton1, we selected four combat sports (boxing, taekwondo, free-style wrestling, and Greco-Roman wrestling) for inclusion into the meta-analysis. Note that taekwondo was introduced as an Olympic sport in the year 2000 and therefore the year 1996 included three combat sports rather than four. In addition, we excluded all pool matches for Greco-Roman and freestyle wrestling, in order to make our approach to the data consistent with Hill and Barton1. The fact that these are pool matches, rather than knock-out matches, makes them qualitatively different from the other competitions. Furthermore, there were a number of ‘dead rubbers’ where one or both of the contestants knew that they were already eliminated from the competition. As a consequence, the motivation and commitment of one (or both) of the contestants could be diminished leading to artificial asymmetries in the fight. Multiple clothing colours were allowed for wrestlers at the 2016 and 2020 Olympic Games, instead of wearing the traditional red and blue attire; hence we excluded these data as they are no longer comparable to other years. Applying these criteria resulted in a total of 23 competitions.

Criteria for inclusion of World Boxing Championships

Nine World Boxing Championships (hereafter WBC) were included in the meta-analysis. Our starting point was WBC 2005 as earlier results were not available. Thus, we included Mianyang 2005, Chicago 2007, Milan 2009, Baku 2011, Almaty 2013, Doha 2015, Hamburg 2017, Yekaterinburg 2019, and Belgrade 2021. All matches were eligible to be included in the analysis but see the coding protocol for more details.

Coding Protocol

Method of Winning

The coding scheme developed by Hill and Barton1 was used but there may nonetheless be minor numerical differences in the results reported here and the original results as a consequence of using different statistical software. The main aim of the coding scheme was to identify and exclude walkovers. A walkover was defined as the awarding of a victory to a contestant as a consequence of the other contestant being disqualified, having withdrawn from competition, having forfeited, retired, or being injured before the match. As colour of attire is unlikely to have played a role in these situations, we decided to exclude these competitions from the analyses. The following categories were either included or excluded by sport.

Boxing

We included victories by PTS (points), WP (win on points), KO (knockout), TKO (technical knockout), TKO-I (technical knockout – injury), JURY (results determined by jury votes), TB (tiebreak), RSC (referee stop contest), RSCH (referee stop contest – head blows), RSCI (referee stop contest – injury), RSCO/RSCOS (referee stop contest – outclassed/outscored). However, victories attained by ABD (abandon), (BDI/BDSQ (both disqualified), DQ/DSQ (disqualified), NC (no contest), RET (retirement), and WO (walkover) were excluded.

Taekwondo

Victories by KO (win by knockout), PTF (win by final score), PTG (win by points gap), PTC (win by points ceiling), PTS (win by points), SDP (win by sudden death point), GDP (win by golden point), SUP (win by superiority), RSC (win by referee stop contest) were included. Contests that were excluded involved DSQ (win by disqualification), PUN (win by punitive declaration), and WDR (win by withdrawal).

Greco-Roman and Free-style wrestling

All competitions were included that were obtained through PP (victory by points, the loser with technical points), PO (victory by points, the loser without technical points), ST (great/technical superiority – a difference of 10 points [2000;2004] or 6 points [2008;2012] – the loser without points), SP (technical superiority, 10 points difference, the loser with points [2000, 2004], victory by technical superiority with the loser scoring technical points [2008, 2012]), TO (victory by fall [2000; 2004]), VT (victory by fall [2008, 2012]), and VB (victory by injury). Excluded competitions included E2 (both wrestlers are disqualified for violation of the rules), EV (disqualification from all competition for violation of the rules), EX (three cautions or violations of the rules or three cautions ‘0’ due to error against the rules), PA (injury default), VA (victory by withdrawal), VF (victory by forfeit), EF (victory by forfeit, the loser is not classified).

Points

If the contest was won on points, then we also coded for the number of points obtained by both athletes and calculated the absolute points difference.

Quartiles and tertiles

Note that the matches won by (technical) knockout (KO), or referee stops contest (RSC), were assigned to the fourth quartile (third tertile) for boxing and taekwondo, while win by superiority (SUP), sudden death point (SDP), and golden point (GDP) in taekwondo were assigned to the first quartile/tertile. Similarly, for Greco-Roman and free-style wrestling, victory by fall (TO, VT) and victory by injury (VB) were assigned to the fourth quartile (third tertile).

Repeated observations

The allocation of coloured uniforms to competitors is approximately random. Evidence for this can be found in the International Boxing Association (IBA)’s Technical and Competition Rules document, the United World Wrestling (UWW)’s International Wrestling Rules document, and in the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF)’s Standing Procedures for Taekwondo Competition at Olympic Games document. However, even with random allocation, the same individuals can appear multiple times, and this could violate the principle of non-independent observations. Yet, taking repeated measures into account using multilevel modelling is complicated by the fact that one typically would want at least 20 observations per individual to reliably estimate random effects54. However, in our data, the number of observations per competitor increases as a function of the outcome (win vs. lose), with only athletes winning at least once appearing multiple times. In fact, in a knock-out competition, most competitors appear only once (they are eliminated in the first round); even the gold medal winner would not meet the minimum number of required observations. Also, we set out to examine the effect following by and large the methods of Hill and Barton (2005). If we alter the approach to analysing the competition data, then it becomes harder to compare the current results to the original results. However, unless there is a mechanism where assignment of colour is tied up with the individual (for example, higher seeds are more likely to receive and then keep red uniforms), there would not be any potential for a directional bias to occur. Even if this scenario were to occur, a dependency caused by the same individuals appearing multiple times likely makes our estimate somewhat less precise but would not introduce a directional bias. As stated by Peters and Mengersen (2008)55: “These results suggest that violating the independence assumption when meta-analysing repeated measures data can lead to estimates of effect that appear to be more precise than the whole evidence suggests.” (p. 947). That is, our confidence intervals would be narrower without taking dependency into account (appearing more precise than warranted) and would be broader (less precise) when we do take dependency into account. If anything, most of our results support the null hypothesis, having broader confidence intervals would provide even stronger evidence for this null hypothesis.

Effect size

The effect sizes denote the proportions of bouts won by red contestants. In instances where a red contestant emerged victorious, a value of 1 was assigned to that match. Conversely, when a blue contestant won the bout, we assigned a value of 0 to that match. In the analyses and in the plots, the effect sizes have been computed by taking all individual bouts within that specific tournament and sport (e.g., “Olympics 2008: boxing” represents one effect size). We did not compute averages within each weight class as an intermediate step in obtaining the effect sizes.

Related

Jets complete head-coaching interview with Rex Ryan

The Jets have concluded their interview with Rex Ryan to be the team’s next head coach.Ryan identified himself as a candi

Disney, FuboTV And Implications Of A Surprising New Sports Deal

Group of fans cheering while watching match in stadium.getty Disney and FuboTV just kicked off the 2025 media and entertainment M&A sweepstakes with the ann

Patriots interviewed Pep Hamilton for head coach on Tuesday

The Patriots have not wasted time in starting their head coaching interviews. According to a report from NFL Media, New Eng

Report: Patriots interviewing Byron Leftwich for head coach

The Patriots are speaking with someone who has a strong connection to their most famous quarterback about their head coachi