A Laws-Jobs-Cash framework for gender and youth-based economic transformation in Africa

This essay opens Chapter 3 of Foresight Africa 2025-2030, which explores how to transform Africa’s demographic advantage into greater economic and social prosperity by investing in women and youth and by dismantling structural biases and barriers.

The litmus test for any functioning economy is how the members of the least advantaged communities fare.1 If African women, one-half of the continent’s population and often the least advantaged members in their societies, are not thriving, African countries cannot thrive or achieve any of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).2 Often, women act as the so-called canary in the coal mine, and declining outcomes for women can be a crucial leading indicator of socioeconomic woes to come. These issues are particularly pressing given the status of the continent as the world’s youngest. Policies that focus on improving the well-being of the growing share of young women will be key to economic growth.3

If African women, one-half of the continent’s population and often the least advantaged members in their societies, are not thriving, African countries cannot thrive or achieve any of the Sustainable Development Goals.

While African women have experienced some gains in important economic development outcomes like education, with the gender gap in primary school enrollment having closed in the last few years,4 there are still significant gaps across multiple key economic areas in many countries. I focus on three key gaps and opportunities for policymakers to boost economic growth here and introduce a Laws-Jobs-Cash (LJC) framework for gender and youth-based economic transformation in Africa. The framework is outlined as follows:

I. Laws

Securing the legal rights of women is good economic policy and will improve economic development in African countries.

Having more women involved in the formal economic sector will boost countries’ GDPs by increasing firms’ access to skilled labor and the introduction of more diverse and innovative ideas5 and converting gains from women’s increased educational attainment into skilled labor to boost firm productivity.6 An important way to get more women involved in this way is by increasing women’s access to labor markets. Doing this will require two main elements: a) providing women with resources to access labor markets easily and in a less costly way, and b) changing social norms and biases against women to ensure that women can access these markets.7 A low-cost way to achieve both of these outcomes without direct government intervention in the labor markets is for governments to intervene with laws in housing markets, labor markets, and politics in the following ways:

- Pass anti-discrimination laws that ensure that women are not discriminated against in the workplace for any gender-based reason—e.g., customer discrimination, hiring manager bias, or discrimination based on marriage or pregnancy status. Every country should fund and maintain the equivalent of an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission that is tasked with monitoring firms in the public and private sector and prosecuting firms that violate gender discrimination laws. Some countries already do this, and we have seen some progress, though more legislation is needed across Africa. One recent success story comes from Nigeria where in 2023, in the case of Omolola Olajide v. The Nigerian Police Force & two others (unreported Suit No: NICN/AK/14/2021), the court affirmed that it was unlawful to dismiss an unmarried pregnant woman after a female police officer was dismissed from her position after getting pregnant.8 Her initial dismissal was based on a pre-existing police law that forbade unmarried female police officers from getting pregnant, a law that was very clearly discriminatory against women. Ensuring that federal laws are created to protect women from discrimination in the labor market is an important first stage for boosting female employment and subsequent economic growth within countries.9

- Change inheritance laws to guarantee women’s right to inherit land and property. Access to land and property provides a key source of wealth that allows women to not only guarantee their own financial stability but also that of their children, especially their daughters. A plethora of research has shown that this improved financial stability leads to higher education, employment, and improved life outcomes for future generations.10

- Pass and enforce anti-discrimination laws that will prevent landlords from discriminating against women by refusing them housing. Housing discrimination negatively impacts women’s labor market opportunities and labor force participation in ways that reduce economic output and growth.11 Lack of access to adequate housing means lowered access to work. Housing discrimination against women, especially young women, is rampant in many African countries.12 Stories like Damilola Olushola’s—a 32-year-old professional Nigerian woman who was repeatedly refused housing because of landlords’ refusals to rent to women (and especially women without male partners)—are unfortunately quite common.13 Olushola’s difficulty in finding housing increased her costs of commuting to work, which then limited her employment and income generation opportunities. Gender-based housing discrimination against women by landlords should be illegal, as it not only reduces women’s access to the aforementioned opportunities, but also increases women’s exposure to sexual harassment and gender-based violence by forcing them into unsafe housing.14 In these contexts, any woman without a male partner—be they unmarried, a widow, divorced, or married but living apart from their male partner—becomes increasingly marginalized and vulnerable to exploitative, discriminatory landlords and increasingly at risk of becoming unhoused and exposed to unsafe conditions.15 This significantly increases risk of violence against women as women are forced to rely entirely on men for access to safe housing.16

- Make it illegal for landlords to demand that renters must pay rents up to a year in advance. These policies disproportionately harm women as women, on average, earn lower wages than men.17 In most parts of the world, rents are paid monthly. As of 2019, four out of 19 major African countries required annual upfront payments: Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana, and Sierra Leone.18 African countries are lagging the rest of the world on this issue. Some countries, however, are leading the region on policies that prevent these types of exploitative rental practices, with Botswana and South Africa not requiring annual upfront payments.19 And others, like Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, and Senegal, have more flexible rental arrangements with 1-3 months upfront payments required.20 Countries should learn from their peers in the region and pass laws to eliminate the annual or several months upfront rental payments requirement to boost economic development.

- Diversify the legislative body in African countries, as this will be a crucial part of enabling points 1-4 to pass in a less costly way. Whether it be in the private sector or public sector, we have research-based evidence that having more women in power can increase productivity and economic outcomes.21 Women in political office are often the bedrock of economic transformation, and yet women are underrepresented in parliaments across Africa (Figure 15) with women making up just 27% of legislative parliamentary seats in sub-Saharan Africa, versus 36% in Latin America and the Caribbean and 33% in Europe and North America.22 Countries should institute affirmative action policies that reserve political seats for women and educate women and men (through the primary to university school curriculum) on the importance of engaging women politically and civically for economic development. Significant gaps remain across most African countries, with many countries having relatively low shares of women in lower parliament relative to the continent mean (25%, Figure 15). Nigeria, the continent’s most populous country, posts especially dismal numbers, with women making up just 3.9% of lower parliament as of 2024, placing the country in the bottom 10 countries in the world for female representation in lower parliament. Rwanda, where women hold over 61% of seats in parliament, is a leader in this regard as the country with the highest share of women in lower parliament in the world. This was achieved through the implementation of a quota law requiring 30% of all elected positions be held by women.23 We have strong evidence that involving more women in politics and the legislature can improve women’s political participation and the passing of more gender-equal laws and welfare-enhancing economic policies in countries.24

In focusing on these laws, a key point to note is that while the emphasis in the last few years has been on the benefits of technology for promoting gender equality, youth employment, and structural transformation, countries and governments cannot tech their way out of cultural transformation. Laws are necessary to change social norms that can cause gender inequality to persist even in the presence of technological innovations in labor, housing, and financial markets.25

II. Jobs

Governments should invest in more public-private partnerships that leverage the potential for technology to boost women’s employment and improve economic growth. Policymakers can do this in two major ways:

- Partner with online hiring platforms to encourage more applications by female applicants and more engagement with formal sector jobs and improve the job match between female applicants and employers. Policymakers can do this in many ways—for example, by boosting platforms with proven records on matching firms and job applicants on official government job platforms. Online job portals like Jobberman in Nigeria and Ghana or Brighter Monday in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda serve millions of job seekers, particularly young job seekers between the ages of 18 and 40, and can provide both ad targeting, information sharing, and skills training services that can help female applicants and young people connect to jobs.26 These platforms can also help employers match qualified female applicants more easily. Governments can subsidize access to these platforms for new, young, female job seekers (e.g. by connecting to job seekers at public secondary schools and public universities) and female job seekers in rural areas or from low-income backgrounds. Engagement with the platforms would also allow governments to monitor labor market discrimination against women in a less costly way, building further on the L in the LJC framework.

- Lower legal and financial barriers to accessing grants and loans for female entrepreneurs. Access to finance for female entrepreneurs is relatively low globally.27 Women in Africa are some of the hardest working entrepreneurs in the world. Nearly 50% of women in the non-agricultural labor force are entrepreneurs, and Africa is the only region in the world where women have a higher likelihood of being entrepreneurs than men.28 Despite this and Africa having the highest share of female enterprises in the world (26%), female entrepreneurs are more likely to own or work in informal microenterprises. This means they are less able to grow their businesses, often have unstable finances, and lack access to formal lenders and the capital they need to expand, raise their incomes, and boost national employment by creating more jobs in their regions.29

Additionally, more than 60% of countries in Africa lack legal protections that actively prevent discrimination against women’s access to credit.30 This lowers sustainable investment ratings of African countries and subsequently reduces the amount of private capital inflows into African countries. By World Bank estimates, closing this gender gap in employment and entrepreneurship could raise global GDP by over 20% and would result in significant financial windfalls for countries ready to invest in female workers and entrepreneurs.31

III. Cash

Governments must create targeted social safety nets for women and expand women’s financial access by lowering regulatory and infrastructure barriers to opening bank accounts, especially mobile money accounts.32 This can be achieved through the following two recommendations:

- Create targeted social safety nets. Not only do African women face gender discrimination in housing and labor markets as described above, but also in financial markets in ways that combine to lower their income, wealth, and access to financial markets more generally. This has catastrophic implications for their vulnerabilities to shocks like floods, epidemics, and droughts that are expected to get worse and more frequent due to climate change. These climate-induced disasters disproportionately affect women and girls. Women and girls experience worse and more prolonged negative effects, including higher mortality, lowered education, and lowered income in the aftermath of these shocks.33 However, research-based evidence shows that targeting cash grants to women can help alleviate the negative effects these disasters have on women and subsequently entire households and economies.34 A targeted social safety net that directs cash grants to women and female-headed households, especially during disasters, is good economic policy that both reduces gender inequality, guarantees safety and economic well-being for young people, and promotes long-run, sustainable development.

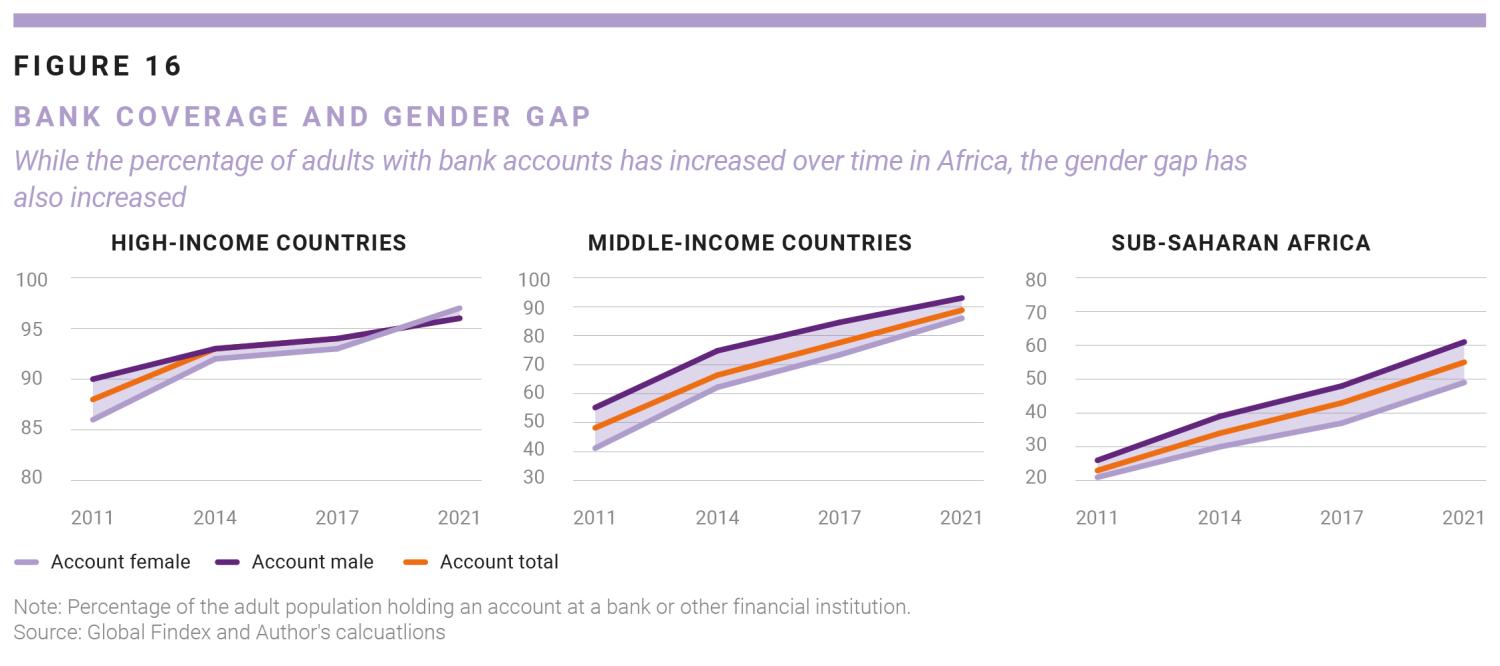

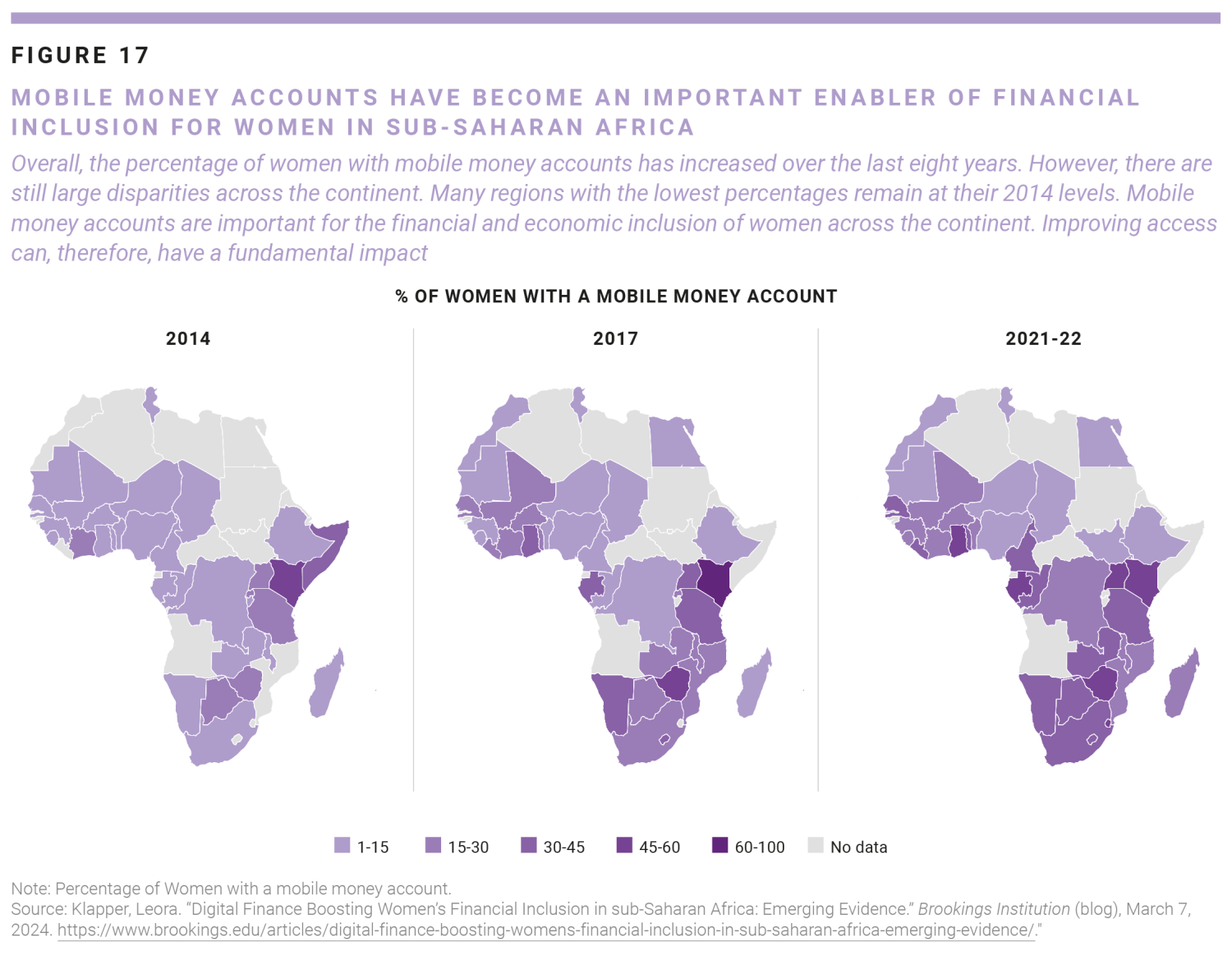

- Ensure that all women have access to bank accounts. While there have been improvements in financial access across Africa, with 55% of Africans having access to bank accounts in 2021 compared to 23% in 2011 (Figure 16), there remains a gender gap in bank access, with the gap increasing to 12% in 2021.35 While mobile money accounts provide a promising avenue for improving women’s financial access (Figure 17), women, who are often poorer than their male counterparts, also have less access to the information and communication technology that would improve their access to these accounts. Here as with employment, policymakers have a twofold opportunity to invest in economic transformation by first, partnering with mobile money firms to boost awareness and information about how women can access these mobile money accounts, and second to create and enforce regulation that makes it illegal to discriminate against women and prevent women from accessing banking services. Part of the regulation is to invest in regulatory bodies that monitor fraud in mobile money markets to ensure that women are not being overcharged in mobile money transactions.36

African policymakers that focus on the three pillars of the LJC framework (Laws, Jobs, and Cash) for gender and youth-based economic transformation will be best positioned to boost their countries’ economic growth prospects and realize outsized gains for all populations in their regions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Related

A top recruiter says sports marketing roles are hot right…

Jobs are opening up in the sports industry as teams expand and money flows into the industry.Excel Search &

Public employees and the private job market: Where will fired…

Fired federal workers are looking at what their futures hold. One question that's come up: Can they find similar salaries and benefits in the private sector?

Mortgage and refinance rates today, March 8, 2025: Rates fall…

After two days of increases, mortgage rates are back down again today. According to Zillow, the average 30-year fixed rate has decreased by four basis points t

U.S. economy adds jobs as federal layoffs and rising unemployment…

Julia Coronado: I think it's too early to say that the U.S. is heading to a recession. Certainly, we have seen the U.S. just continue t