When cocaine ruled the NBA: ‘Drugs were everywhere, it was like a fad’

The anecdote is relayed by none other than Michael Jordan in The Last Dance, the Netflix documentary about his final season with the Chicago Bulls. In 1984, the then-rookie Jordan, who would go on to have an historic impact on the sport, found himself in a hotel, on the eve of an away game. He looked for his teammates and knocked on doors until one of them opened. “I walk in, and practically the whole team was in there. And it was like, things I’ve never seen in my life as a young kid. You got your lines [of cocaine] over here, you got your weed smokers over here, you got your women over here. So the first thing I said, ‘Look man, I’m out.’ Because all I could think about was if they come and raid this place, right about now, I’m just as guilty as everybody else that’s in this room,’” Jordan recalled.

Not in vain, before the arrival of the player who would become their biggest star, the Bulls were known as “the travelling cocaine circus.” The publication in the USA of Banned, the memoirs of Micheal “Sugar” Ray Richardson, the first player to be banned from the sport for drug use, has brought back into focus an era in which the NBA was almost better known for the excesses of its players off the court than for the spectacle they provided on it.

Richardson, drafted fourth overall in 1978, was not a huge star, but he was a highly-regarded point guard who had been selected for the All-Star Game four times. However, in the 1985-86 season, his career was cut short: after failing a third drug test, he was banned from the league for life, an unprecedented punishment that David Stern, elected NBA commissioner in 1984, used as a warning to players: the era of excess was over. By then, drug use among NBA players had grown so much that in 1980, The Washington Post published an article in which it estimated that between 40% and 75% of league players used cocaine, while one in 10 smoked marijuana.

‘Let’s get together when the game is over’

Those numbers, as incredible as they may seem in 2024, don’t seem far-fetched according to some of the confessions from players like Richardson. “During warmups guys on different teams would say, ‘Yo, man, I got what you’re looking for. Let’s get together when [the game] is over’ […] Drugs were everywhere — it was like a fad,” the former player told The Guardian newspaper. To the point that, as he explains in his memoirs, some teams began to spy on their players, such as when Robinson was traded to the Golden State Warriors. “When I got to Oakland, I was living in a Holiday Inn, getting high almost every day, especially when I was injured. I also immersed myself in the area’s famous nightlife, so much so that the Warriors began hiring private detectives to follow me.”

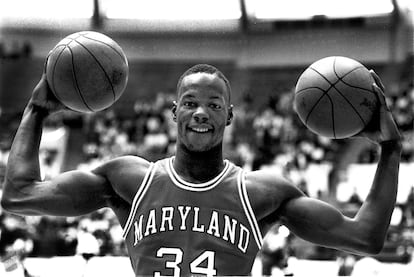

Robinson’s was the most notorious case — due to the punishment he received — but by no means the only one that came to light at the time regarding drug use by NBA players. Marvis Barnes, nicknamed “Bad News,” was a power forward who played in the 1970s and 1980s for several teams including the Detroit Pistons and the Boston Celtics. His biography, Bad News, recounts how he went from being an important player in the league to spending five years in prison for dealing drugs. However, even more tragic was the story of Len Bias. Considered one of the most promising college players of his generation, he was picked second overall in the 1986 NBA Draft by the Boston Celtics. After the ceremony, he decided to celebrate with some of his teammates. Less than two days after securing his future as an NBA player, he suffered a cardiac arrhythmia caused by cocaine use that ended his life.

Bias’ death and Robinson’s ban coincided in the same season, marking a turning point in the consumption of prohibited substances in the history of the competition. Stern’s plans were to turn the NBA into a worldwide entertainment product, but first he had to put a stop to what happened after the games. Thus, he established drug tests in each game and made treatment and rehabilitation programs available to the players. In the short term, he did not end all cases of drug use in the league, but he did change its dynamics.

Since the 1990s, the substance that has appeared most frequently in NBA tests is marijuana and derivatives, with regular sanctions (both sporting and financial) imposed each season. Until now. Last year, the players’ association and the NBA signed an agreement by which, for the first time, the use of cannabis for recreational purposes will no longer be monitored in tests. It is the first concession, a sign of the times, of a competition that did its best to forget a wild period that, from time to time, still resonates.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Related

NBA: Mark Cuban says he would have asked for more…

Feb 13, 2025; Dallas, Texas, USA; Mark Cuban laughs during the second half of the game between the Dallas Mavericks and Miami Heat at American Airlines

NBA Scout Reveals Why Celtics Can Easily Beats Knicks in…

The Boston Celtics are one of the teams who are expected to be a contender at the end of the season. They are the defending NBA champions, so they feel like the

Nikola Jokić gives peak Nikola Jokić interview with Scott Van…

Nikola Jokić is still rewriting the record books — and treating it like just another day at the office. In a 149-141 overtime win over the Phoenix Suns

Knicks’ Struggles vs. NBA’s Elite Explained

The New York Knicks are one of the best teams in the NBA, but as of late, they have been defined more by their struggles than their triumphs.The Knicks are 0-7