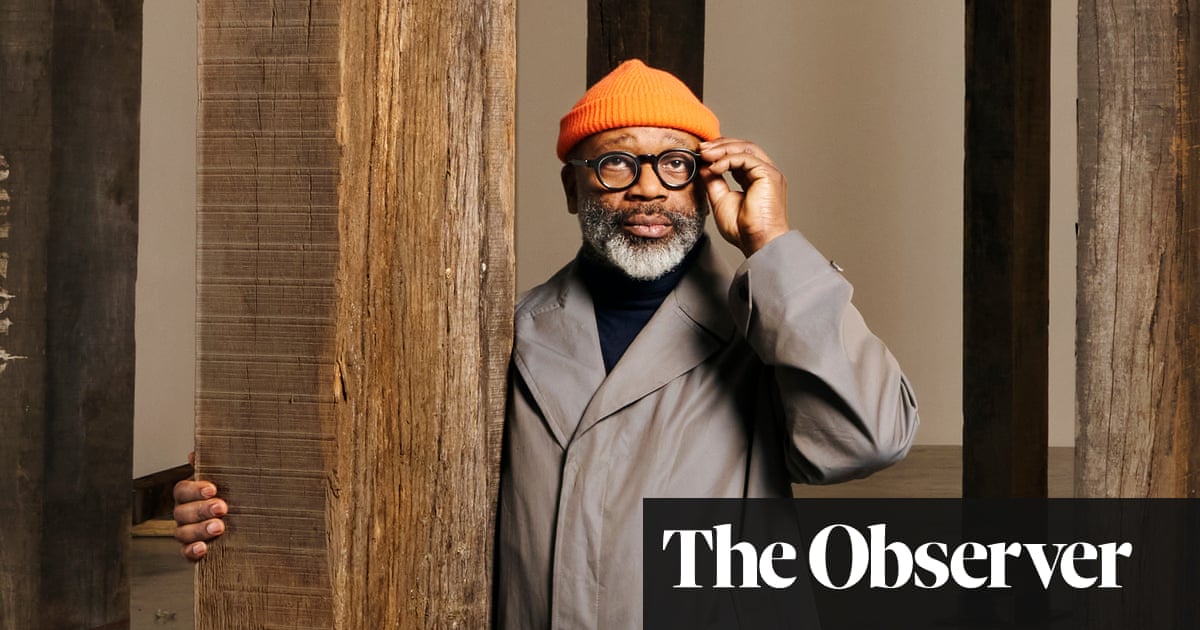

Theaster Gates: ‘I’m an artist. It’s my job to wake things up’

When you are in this line of work, a question people sometimes ask is: “Of all the people you have interviewed and written about, who was the most inspiring?” And when they do, my memory often goes back to a day I spent 10 years ago driving around the south side of Chicago with the radical potter, and revolutionary urban planner, and guerrilla archivist, and situationist gospel singer, Theaster Gates.

At the time, Gates, then 41, charismatic and intellectually irrepressible, was about seven years into a project to transform the neighbourhood in which he lived – blighted by years of neglect and unemployment and poverty and related crime – into a working community of makers and artists, a place that looked after itself. While employed as a city planner and academic at the University of Chicago Gates had, he explained to me as he drove, become haunted by a fundamental question: why is it so often that the people with the least amount of imagination and the most concern for the bottom line – real estate developers – get to choose how to transform derelict urban areas? Why not the people who might care about those areas most: the citizens who grew up there and live there?

To answer this question Gates had some years earlier begun buying one or two of the empty houses along the street where he lived: the first with all of his savings – $18,000 – and others with money he raised selling editions of art he started to make (one lucrative line, $5,000 a pop at international art fairs, was a series of shoe-shine stands he made of scrap wood, referencing a whole history of Black-American experience; others were fabulous collages fashioned of reclaimed water hoses from the Alabama fire departments, titled In the Event of a Race Riot). Using that money, he had transformed those houses into places of rough-edged beauty, using reclaimed wood and repurposed furniture. He filled the first – the Archive House – with 14,000 art books bought from a shutdown bookstore. The second – the Listening House – housed all the LPs he had saved from a once-famous local record shop, Dr Wax. He created a soul food kitchen between them, and opened them up to the public.

That initial transformation had, by the time I visited, become a kind of infectious local awakening. The whole neighbourhood had slowly begun to rouse itself and, inspired by Gates’s example, remember just what it was capable of. We visited his studio, which employed 60 craftspeople and the huge, decaying porticoed former bank building that he had acquired from the city fathers for a dollar, and was ambitiously restoring as a gallery space using funds from selling bonds made from the marble tiles of the building’s former urinals – a nod to Marcel Duchamp – inscribed “In art we trust”. When we met, Gates was in high demand exporting that vision to beleaguered communities in the American rust belt and beyond.

It seemed to me then that his work was a powerful broadside to that juvenile mantra of tech bros and venture capitalists, the one that claims progress comes from “moving fast and breaking things”. Gates was modelling a proper human alternative: stay put and preserve things, use all of your agency to make them live.

Last week, 10 years on – a decade in which the hope placards of the Obama presidency have long been abandoned – I met up with Gates again, at the White Cube gallery in Bermondsey, south London, where he is putting together a large-scale exhibition of some of his current thinking. In the week that the 47th president was sworn in, here Gates was unpacking from dozens of enormous shipping crates his alternative vision of making America great again.

The exhibition, called 1965: Malcolm in Winter: A Translation Exercise looks back 60 years to the assassination of Malcolm X, but through a particular evocative lens. When Gates put on a show in Tokyo last year, an exhibition partly concerned with the links between the American civil rights movement and Japanese traditions of deep craftsmanship, he was approached by an 87-year-old woman, Haruhi Ishitani, who had come to see it. Ishitani was the widow of a journalist, Ei Nagata, who, along with his wife, had been a lifelong student of Black-American history, an obsessive collector of pamphlets and posters from the 1960s, and the translator of all of Malcom X’s speeches into Japanese. That obsession had been fuelled by the fact that the couple had been in the audience in Harlem on 21 February 1965, when Malcolm X was shot and killed while making a speech. Now that her husband was gone, Ishitani was wondering exactly what to do with the unique archive they had accumulated. Gates’s gallery show had provided the answer: she would donate it to the artist.

Some of that archive, which is in the boxes on the desk and on the floor in the gallery where we are sitting talking, will be displayed in Gates’s Bermondsey exhibition, along with, among other things, some huge architectural sculptures, rudimentary wooden Japanese tea houses and temple spaces. He doesn’t think the timing or the fact of the Malcolm X bequest was down to chance. “I now think maybe the purpose of me doing the exhibition [in Tokyo]” he says, “was, in fact, to meet Haruhi and receive the archive…” He sees his primary role as an artist to tune into some of the “frequencies in the air” at any given moment, and to then “find the right tone to express them – a little less treble, a little more bass”.

If you are wondering, like me, about the connections between civil rights and Japanese pottery, Gates has several answers. Each articulates ideas about quality and dignity. Gates was the youngest of nine children, the first boy in the family. His mother was a teacher and his father worked as a roofer. From his mother he learned the importance of wide reading, from his old man the importance of doing even unseen things, dirty jobs, properly and well. His first plan was to be a potter, and in pursuit of that he spent some months aged 25 in Tokoname, one of the ancient centres of Japanese pottery. “I thought I was a pretty good intermediate,” he says, “but when I saw these 90-year-old dudes working, I realised that I knew nothing at all.” That discipline, the unwritten standards of the unknown craftsman, informed his work, and triggered connections with the kind of rigour that had inspired the civil rights activists he had admired.

“The question here,” he says gesturing around the gallery, “is how do you translate political values into aesthetic values? I’m not a historian, I’m an artist. It’s my job to wake things up. If I was putting 13 paintings on the wall, it would be a lot more straightforward. But this,” he points at the boxes of archival material, “suits me. The idea is to start to discover these things together.”

It is the potential in the archive that interests him, like seeds waiting for rain, and the exciting materiality of it. “An institution would immediately remove these things from the public, take them down and down into the dungeons of a building to keep them protected. But this is activism. These documents want to be active.”

after newsletter promotion

And what better moment for that revival than this week?

“Indeed,” he says. “As the inauguration was unfolding, I was looking at some of this history. And thinking about how assassination had been a way of putting terror into the citizenship. One after another, our leaders were assassinated in front of us. They killed Fred Hampton, Malcolm X, they killed Martin Luther King, they killed Bobby Kennedy. That is a lot of slaughter. So when people then say to me today: ‘The left in America is so weak.’ Well, damn! What we are seeing is how this thing was so effective. These were the people who were saying we could achieve racial unity, we could achieve solidarity. And the regime saw that as a threat and these men were killed.”

Sitting at his desk, Gates rises to his theme. “It doesn’t matter if I’m an artist or a this or a that, a historian who cares, a lawmaker who feels, a songwriter who has a sense of the urgency of the day. They will all now find themselves doing things that an art historian might call socially engaged. And that engagement has to be to resist these contemporary alignments of government with corporations and big technology and communication.”

One of the things Gates’s art insists on is that, at a time when everything is becoming more digitalised and manipulated, it’s a fundamentally political act to say that craft matters, objects matter, handmade things matter.

He opens one of the boxes next to him and passes me a home-printed civil rights calendar from the year 1968, with historical events marked. “Look at that,” he says. “It’s like, ‘They’re going to make us forget these things unless we make something lasting with them.’” I turn to the current week and am reminded that the day of Trump’s inauguration also marked a far more significant date: the annual public holiday that celebrates Dr Martin Luther King’s birthday. The little jolt is a reminder, like all of Gates’s art, that just as other pasts were possible, other dreamed-of futures always, urgently, remain so.

Related

A top recruiter says sports marketing roles are hot right…

Jobs are opening up in the sports industry as teams expand and money flows into the industry.Excel Search &

Public employees and the private job market: Where will fired…

Fired federal workers are looking at what their futures hold. One question that's come up: Can they find similar salaries and benefits in the private sector?

Mortgage and refinance rates today, March 8, 2025: Rates fall…

After two days of increases, mortgage rates are back down again today. According to Zillow, the average 30-year fixed rate has decreased by four basis points t

U.S. economy adds jobs as federal layoffs and rising unemployment…

Julia Coronado: I think it's too early to say that the U.S. is heading to a recession. Certainly, we have seen the U.S. just continue t