The social order of illegal markets in cyberspace: extralegal governance and online gambling in China – Humanities and Social Sciences Communications

Extralegal governance institutions refer to private or nonstate mechanisms, such as norms, rules, organizations, and behavioural equilibria, which are used to mitigate risks, promote cooperation, and deter opportunism (Dixit, 2004; Leeson, 2008). This section first examines the risks faced by participants in illegal markets and how these risks evolve when illegal transactions move online. It then discusses the governance institutions participants could use to mitigate these risks in both offline and online social settings.

Risk and uncertainty in illegal markets

Illegal markets emerge and flourish in the teeth of state prohibition. These markets supply in-demand goods or services that are unavailable in the legal marketplace (Schelling, 1971). State prohibition of production, supply and distribution of these goods and services generates enormous opportunities for criminal entrepreneurs (Dewey, 2019), but prohibition creates substantial risks for participants. These risks fall into two categories. First, participants in illegal markets face opportunistic behaviour, such as fraud, betrayal, and free-riding, which cannot be resolved by state institutions, such as the police and courts. Compared with participants in legal markets, illegal market participants are less inhibited about misconduct and are more likely to engage in opportunistic behaviour for a quick profit (Campana and Varese, 2013). Even though cooperation generates profits and satisfies individual needs, potential participants will hesitate if they see widespread distrust and opportunism in the illegal market. For instance, a buyer has less incentive to risk paying in advance when they are uncertain about whether the seller will deliver services or goods as promised; likewise, a lender is unwilling to lend money to a new borrower without sufficient collateral.

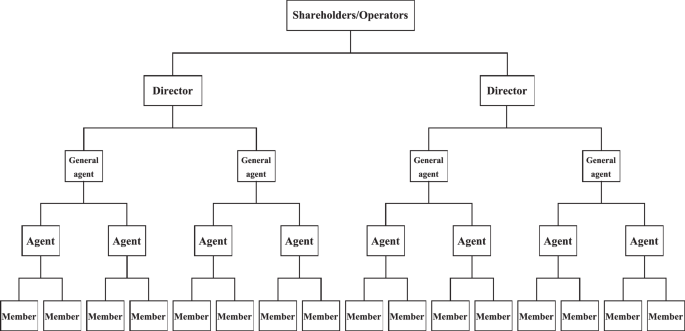

Second, illegal markets undermine the rule of law and state legitimacy, making them subject to police crackdown and government suppression. In authoritarian China, the government employs campaign-style law enforcement to deal with crime-related problems, including illegal markets (Trevaskes, 2007; Wang, 2020a). Harsh and unpredictable law enforcement poses the greatest threat to illegal market participants, especially suppliers and distributors of illegal commodities and services; they face a high risk of incarceration, and profits from illegal exchanges can be confiscated. State law, especially criminal law, specifies different types of criminal punishment and different severity levels for different roles: some participants are defined as producers or suppliers, some as street-level distributors, and others as customers (see Wang, 2020b). For instance, in China, operators or agents of online gambling websites are charged with operating illegal gambling businesses (kaishe duchang zui) and are subject to a maximum five-year custodial sentence according to Chinese Criminal Law. In extremely serious cases, offenders may face a maximum ten-year custodial sentence. In contrast, the vast majority of gamblers are not subject to criminal punishment and instead receive, at most, 15 days of administrative detention according to China’s Public Security Administration Punishments Law. This differential punishment divides market participants into distinct groups: high-risk actors, such as illegal gambling operators, and low-risk actors, such as gamblers. This division affects how market participants interact.

When illegal exchanges move online, both challenges and opportunities increase. On the one hand, network technology transcends geographical boundaries and enables participants to conduct transactions with a much wider group. On the other hand, the anonymity of the Internet boosts opportunistic behaviour, such as fraud and cheating. Interacting with strangers online is challenging; participants find it difficult ‘to assess trustworthiness or to retaliate should dealing go sour and agreements need to be enforced’ (Lusthaus, 2012, p. 71). Dishonest participants are still able to take advantage of internet anonymity to sell products and services by disguising their identity online, even after cheating their exchange partners (Lusthaus, 2018). To make transactions possible, illegal online entrepreneurs have to develop strategies to signal their trustworthiness or make credible commitments.

Even though anonymity and identity shielding enable illegal entrepreneurs to hide behind the screen, making it harder for police to investigate illegal exchanges, illegal online entrepreneurs still risk detection, for two reasons. First, network technology helps local law enforcement agents communicate with their counterparts overseas to follow online clues across jurisdictional boundaries. Second, the traditional way of mitigating risks of criminal prosecution—bribing police officers—does not work so well online; it is harder for criminals to suborn police officers in distant geographic areas, as they are unable to build trust through face-to-face contact.

It is worth noting that those who make transactions in cyberspace not only interact in a virtual world but may also collaborate offline (Lusthaus, 2018; Lusthaus and Varese, 2021), often using pre-existing social relationships. Specifically, criminal entrepreneurs often have to rely on their interpersonal networks to find potential clients or partners. Most advertising strategies and promotional approaches adopted by legitimate businesspeople are unavailable to criminal entrepreneurs, so sellers must advertise and promote their products or services among their acquaintances. Likewise, it is less feasible for criminal entrepreneurs to recruit employees in the formal labour market. Instead, illegal sellers rely on personal relationships to recruit trustworthy collaborators and employees (Leukfeldt et al. 2017a, 2017b).

Governance mechanisms in offline and online contexts

The operation of illegal online markets is sustained by a range of governance institutions. This part investigates extralegal governance institutions from offline and online perspectives, although the effectiveness and performance of these institutions can vary according to context.

Offline extralegal governance institutions

In the offline world, participants in illegal markets have developed a set of extralegal governance mechanisms to enforce agreements, overcome opportunism, and minimize the risk of criminal punishment. One of the most frequently used offline mechanisms is reputation, which relies on the transmission of interpersonal-based information. Before initiating transactions, participants evaluate the trustworthiness of potential partners by gathering information about their reputations, including credibility, competence, and past behaviour. In practice, information is transmitted through gossip in relational networks (Giardini and Wittek, 2019). Unsurprisingly, many participants decline to interact with a person who has a record of cheating or betrayal. Given that reputational information is transmitted through close social relationships, it is reasonable for a person to behave honestly and cooperatively if they value the earnings potential of future interactions (Dixit, 2004; Greif, 2006). The interpersonal-based reputational mechanism is more efficient when the network is tight and small; it becomes expensive and inefficient when the network size significantly increases or the network becomes more socially and culturally diverse (Ellickson, 1991).

When participants in illegal markets want to exchange with those outside their close social networks, they need to solve the problem of asymmetric information, which is caused by the lack of reliable information about each other’s trustworthiness (Leeson, 2008). In such circumstances, participants need to develop strategies to signal trustworthiness. By investing in a credible signal, participants can convince potential exchange partners that they are trustworthy in the sense that they are not playing a one-shot game and will behave cooperatively, honestly, and patiently instead of opportunistically (Gambetta, 2011; Gintis et al. 2001; Lin et al. 2024). Empirical evidence suggests that people, including criminals, have developed credible signals to enhance cooperation when interacting face-to-face. These signals range from investments, such as criminal rituals (Skarbek and Wang, 2015) and gift-giving (Posner, 1998), to implicit cues of intrinsic motivation or emotion, such as eye contact, a sincere smile (Cheng et al. 2020) and tattoos on the face or neck (Gambetta, 2009). Nonetheless, it is not always possible to ensure the credibility of such signals, because they can be simulated by opportunists who can reap the benefit from a one-shot game. Trustworthiness signals are clearly not a panacea, and other mechanisms are needed to secure cooperation.

Threats and violence are commonly used to enforce compliance in criminal markets such as offline gambling (Wang and Antonopoulos, 2016), drug dealing (Durán-Martínez, 2017), and kidnapping (Shortland, 2017). Organized violence, as a means to provide protection and achieve informal control, is often provided by professional third parties such as gangs or mafias (Gambetta, 1996; Varese, 2011). Due to their capacity to use violence, gangs are often invited to get involved in illegal markets to enforce contracts, deter fraud, and solve disputes (Andreas and Wallman, 2009). In many scenarios, the mere threat of violence is sufficient, especially when participants can credibly display their toughness or convince potential partners of the toughness of their confederates (Gambetta, 2009).

Nonetheless, the purchase of gang protection and the use of violence have several drawbacks. First, illegal entrepreneurs have to pay to obtain private protection or criminal enforcement, and rates can be high. Second, extensive use of violence attracts police attention. The risk of criminal punishment is particularly high in countries where the state tries to monopolize the use of coercive power within its territory (Barzel, 2002; Wang, 2020a; Weber, 2004). Low-risk actors, who face less severe punishment if arrested, can blackmail high-risk actors by threatening to report them to the police, putting high-risk actors in a precarious situation. In this context, an act of violence and the use of gang methods are compromising information that can be exploited by others (Campana and Varese, 2013, p. 266; Gambetta and Przepiorka, 2019). Finally, violence becomes less effective when illegal entrepreneurs shift transactions online because in-person enforcement becomes more expensive and less feasible (Wang et al. 2021).

In addition to market-based risks such as opportunistic behaviour, participants in illegal online markets face the threat of prosecution. To mitigate this risk, they often resort to bribing state agents (Wang, 2020a). Corrupt police officers can offer protection to illegal entrepreneurs in two main ways. They can choose not to investigate individuals with whom they have corrupt dealings, and, taking advantage of their privileged access to information, they can inform illegal entrepreneurs of imminent police operations in their jurisdiction. Nonetheless, purchasing protection from stage agents is not sufficient for securing the operation of illegal markets in cyberspace, and therefore other strategies are called for.

Extralegal governance institutions in the online world

As participants move their interactions online, they adopt governance mechanisms that are effective in offline markets to function online. The first of these is the system-based reputation mechanism. Unlike the interpersonal-based reputation mechanism, which relies on information provided by acquaintances, in the system-based reputation mechanism strangers rate and review distant partners, allowing external parties to assess the trustworthiness of potential partners. System-based reputation mechanisms are widely used in online markets. They include not only rating and feedback systems used on sharing economy platforms, for example, e-commerce sites such as eBay, Amazon, and Alibaba (Dellarocas, 2003; Standifird, 2001), but also comments made in the forums and websites of cybercriminal markets, relating for example to stolen data, drug dealing, and botnet services (Décary-Hétu and Dupont, 2013; Hardy and Norgaard, 2016; Holt et al. 2015). However, reputation information can be seen as public goods (Bolton and Ockenfels, 2009); participants might have a tendency to free-ride on evaluations provided by others and lack the incentive to contribute to the information pool (Lev-On, 2009).

Similar to the offline context, signalling trustworthiness is a useful way for participants in cyberspace to show potential exchange partners their reliability and competence. Online signals point either to the credibility and ability of individual participants, such as illegal entrepreneurs, or to online marketplaces, such as websites or platforms. Trustworthiness signals are as expensive for individual entrepreneurs to produce online as they are offline. For example, a digital vendor can demonstrate their desire to encourage repeat business by spending time in a forum. Trustworthiness signals also include subtle clues, such as posting personal photos (Ert et al. 2016) and using criminal nicknames that are well-known in illegal communities (Lusthaus, 2012).

Platforms or websites often establish high-profile brands, user-friendly interfaces, institutionalized rules, and formalized programmes to signal their trustworthiness and attract a large number of clients. For example, high-profile brands not only indicate that the platforms have a large number of loyal clients, but they also signify the investment of digital entrepreneurs in advertising, indicating their intention to engage in long-term business (Möhlmann and Geissinger, 2018; Riegelsberger et al. 2007). Likewise, a website that offers effective security technology and a strictly enforced privacy policy can increase the sense of safety for clients and thus their confidence in using the website (Riegelsberger et al. 2007). By contrast, it would not be surprising that clients hesitate to engage in transactions if the payment process of an online marketplace often fails or requires clients to send payment to the private account of a person they do not know.

Online platforms, such as forums, websites, and apps, serve two distinct roles. First, they can act as direct contracting parties, engaging in sales transactions with clients. Second, they can function as third-party enforcers, providing a marketplace for online transactions and associated enforcement services to both vendors and clients. As providers of goods and services, online platforms have to establish themselves as major suppliers of certain commodities by building their reputation and earning the trust of their customers. As third-party enforcers, trustworthy online platforms must address the issue of customer opportunism, where customers may attempt to exploit the platform for their own gain. As previously mentioned, violence is not a credible threat in an online setting, so alternative institutions must be developed. One common mechanism is the use of hostage-taking, which involves demanding a deposit or initial payment as an ex-ante mechanism to deter cheating by either party (Raub and Keren, 1993; Weesie and Raub, 1996). In addition, online platforms must establish clear rules to regulate online transactions, including rating and escrow systems, reporting and refund functions, and sanction mechanisms.

To lower the risk of detection and prosecution, illegal entrepreneurs in cyberspace use Internet infrastructure and network technology to conceal evidence of their activities. Several methods are commonly employed, such as frequently setting up new websites, using others’ accounts, employing web proxies located overseas, and avoiding the use of terms that are subject to police monitoring. However, these strategies can erode clients’ perception of entrepreneurs’ credibility and reliability as well as the services and goods they provide. This highlights the need for market participants to develop shared norms and an understanding of these concealment strategies.

Related

I became a millionaire in my 20s but my sports…

Millions wagered, hundreds of thousands in debt and a pending divorce.Joe C, a native of Chicago, fell into the depths of addictive sports gambling at the age o

Strip executive retiring after 3 decades with gambling giant MGM…

A top executive who oversees multiple properties on the Strip, including one of Las Vegas Boulevard’s most recognizable and successful casino-hotels, is

Danish Government’s Success with Gambling Addiction

Gambling addiction is a growing concern worldwide, with many countries struggling to find effective ways to regulate the industry. Denmark, however, has e

UFC 313 Gambling Preview: Will Magomed Ankalaev end Alex Pereira’s…

Alex Pereira is back! On Saturday, Pereira puts his light heavyweight title on the line against Magomed Ankalaev in the main event of UFC 313. Before that, J