The female travellers who shaped the ancient world

Alamy

AlamyIn the 1800s, a trio of women forever changed the study and understanding of ancient Egypt. So why have their legacies remained overlooked?

In 1864, English travel writer Lucie Duff Gordon stood in her house atop Luxor Temple, looking out the window across the River Nile’s west bank towards the Libyan mountains. Her face basked in the sun while she listened to the cacophony of camels lowing, donkeys braying and dogs barking below. She missed her family, whom she had left at home in London while she convalesced in Egypt’s hot desert climate to ease her tuberculosis symptoms. She lived in the Maison de France, or French House, built by a military contingent in the area around 1815. She loved her self-proclaimed “Theban palace” and wrote letters to her family from its balcony almost daily.

These Letters from Egypt, which richly detailed her time in the country, were published a year later as a book. By vividly detailing Egyptian politics, religious customs and Duff Gordon’s relationships with her Egyptian neighbours, the book stood out as a social and cultural commentary at a time when most women authors wrote fiction. Duff Gordon’s example of travelling – and living – in Egypt as a British woman on her own soon inspired other female travellers to do the same.

A little more than a decade later, novelist Amelia Edwards, moved by Lucie Duff Gordon’s experiences, visited Egypt and published a best-selling travelogue, A Thousand Miles up the Nile. Edwards’ work, in turn, aroused the interest of Emma Andrews, a wealthy American traveller who further advanced archaeology in Egypt at the start of the 20th Century by funding dozens of tomb excavations – many of which are still actively studied today.

Although these three women initially travelled to the country as tourists, they each made a profound impact on Egyptology (the scientific study of ancient Egypt). And in doing so, they not only shaped our views of one of the most important civilisations in the ancient world, but also how tourists travelled to Egypt at the turn of the 20th Century.

Alamy

AlamyThat March, the women stayed several weeks in Luxor. Edwards was drawn to Duff Gordon’s former home. But as she looked up at the pile of bricks atop of the temple, she was shocked at its state. After barely surviving several years of Nile flooding, Duff Gordon’s beloved “Theban palace” was hardly liveable now. Edwards climbed inside and went to the window, looking out over the river and the Thebian plain on the other side. Seeing what Duff Gordon saw, Edwards wrote that the view, “furnished the room and made its poverty splendid”. She dreamed that she could live there: “If only I had that wonderful view, with its infinite beauty of light and colour and space, and its history, and its mystery, always before my windows.”

That was Edwards’ only trip to Egypt, but her poetic travelogue called countless other women travellers to the country. Published in 1877, A Thousand Miles up the Nile would become one of the best-selling travel books of all time. Part travel journal, part well-researched history, Edwards’s narrative vibrantly described the sights along the Nile. But unlike Murray’s guide, Edwards not only recommended visitors stop to view these monuments and sites; she advocated for their preservation for future generations. Her book’s popularity effectively made the Giza pyramids, the Valley of the Kings and other now-famous tombs essential stops for travellers to Egypt for the next 50 years, but more importantly, its wide reach among scholars shaped the study and reception of these sites to this day.

The success of Edwards’ book led her to co-create the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) in 1882. Inspired by Edwards’ goal of exploring to conserve monuments in Egypt, the EES raised money for excavation through subscribers. These subscribers, mostly from the British middle class, received excavation and site reports each year. These reports – containing maps, lists, drawings and new scholarship – have educated and informed the public’s view of ancient Egypt for nearly 150 years.

Alamy

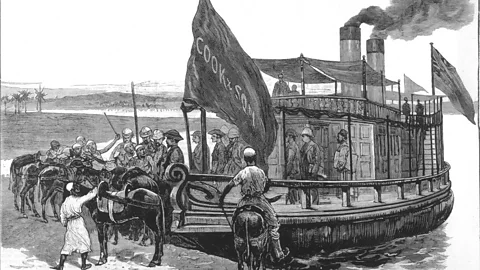

AlamyA Thousand Miles up the Nile also simultaneously stimulated and benefitted from the rise of package holidays offering archaeological tourism. Beginning in 1855, English businessman Thomas Cook’s eponymous travel company started leading people on all-inclusive holidays across Europe. Popular with the upper-middle and aristocratic classes, these package tours encouraged people to travel to destinations like Athens and Rome to not only explore their contemporary culture, but also to witness their ancient monuments and learn about their historical importance. If you were spending a lot of money on a holiday, the argument went, you should learn from it and support the local economies, too.

Cook’s company branched out into Egypt in 1869, making archaeological tourism in North Africa available to the masses – and to women who wished to travel safely alone. By the end of the 1880s, Cook’s company was guiding more than 5,000 people up the Nile each year, closely following Edwards’ own itinerary. Thanks to the popularity of their holidays, the company had control over Nile boat travel for all visitors.

In 1889, 15 years after Edwards had departed Egypt, Andrews and her partner, Theodore Davis, (two American millionaires and archaeological collectors) arrived in Egypt carrying a copy of Edwards’ book and several of Cook’s brochures. The couple were members of the American branch of the EES, which had spread to the United States just a few years after its founding. Inspired by Edwards’s travelogue, they quickly rented and outfitted a private houseboat to take their first trip up the river.

A Thousand Miles up the Nile and Cook’s brochures guided the couple as they sailed up and then back down the Nile. They stopped at all the sites that Edwards (and later Cook) had suggested. Like Duff Gordon and Edwards before them, they immediately fell in love with Egypt. The couple would travel up the Nile each year for the next 25 years. They were the quintessential archaeological tourists: members of the upper class, wishing to have a holiday while also learning about the ancient sites they encountered. They purchased ancient artefacts, amassing huge collections themselves. Andrews was influenced both by her own travels and by Edwards’ exhortation from her travelogue: “We are always learning, and there is always more to be learned; we are always seeking, and there is always more to find.” From 1900 until they left Egypt in 1914, Andrews and Davis would pay for and personally excavate between 25 and 30 tombs in the Valley of the Kings, some of the most consequential archaeological investigations in the country.

Alamy

AlamyLaws for excavations in Egypt at the time meant that most artefacts would be deposited into the Cairo Museum, with duplicates going into the private possession of the patron or archaeologist. In 1905, the pair and their crew found tomb number 46, the tomb of Yuya and Thuya, parents of Queen Tiye (the chief wife of Pharaoh Amenhotep III) and the great-grandparents of Tutankhamun. At the time, this tomb was the best-preserved Egyptian tomb ever found, with most of the funerary equipment still inside. Their stunning coffin masks are still on display in Cairo, and their intact chariot – only the second of its kind ever found – sits just behind them.

The artefacts are important, but Andrews’ diaries are crucial to our understanding of the sites. Her records provide a detailed account of her and Davis’ activity over a quarter of a century. She meticulously chronicled their excavations with maps and daily accounts of their visitors and the artefacts they uncovered. Davis used many of Andrews’ diaries in his own published site reports, never giving her proper credit. Crucially, Andrews also included in her accounts the people ignored by so many male writers: Egyptian workers, antiquities dealers, boat captains and crew. Her perspective is the foundation for the understanding of centuries of Egyptian history.

Andrews’ legacy lives on, too, in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. She and Davis each gave large portions of their collections – more than 1,600 Egyptian artefacts – and their fortunes, to the Met. Each year, millions of visitors view those artefacts, such as the canopic jars from the controversial tomb KV 55. Thanks to Davis’ shoddy excavation practices, archaeologists still cannot conclusively agree on whose mummified remains were inside. There is also a restored decorated water bottle from the funerary procession of King Tutankhamun, one of the few Tutankhamun artefacts outside Egypt. Andrews’ work made these fragments of ancient Egyptian life and death accessible to scholars and schoolchildren alike, giving the West a rare glimpse at how ancient Egyptians honoured the dead.

Alamy

AlamyOur contemporary fascination with and understanding of ancient Egypt is due in no small part to this trio of forgotten women. As with their male counterparts, their work wasn’t without controversy: these were relatively well-to-do folks travelling to, living in and benefitting professionally from Egypt by removing ancient artefacts from their historical homeland. Yet, their often-ignored legacies effectively laid the foundation of modern Egyptology and influenced our understanding of the ancient world from the beginning.

Related

Turkish Airlines and Qatar Airways Suspend Mogadishu Flights Following US…

Home » Airlines News of Qatar » Turkish Airlines and Qatar Airways Suspend Mogadishu Flights Following US Embassy Terror Alert, Raising Security Concerns at

Local tourism destinations grow fast

Men sit at the Doha Corniche backdropped by high buildings in Doha on March 3, 2025. Photo by KARIM JAAFAR / AFP DOHA: Local tourism destinations are g

Hajj, Umrah service: Qatar Airways introduces off-airport check-in for pilgrims

Image credit: Supplied Qatar Airways has introduced an off-airport check-in

IAG, Qatar Airways, Riyadh Air, Turkish Airlines, Lufthansa & more…

Turkish Airlines – a Corporate Partner of the FTE Digital, Innovation & Startup Hub – is charting a course to rank among the top 3 global airlines for