Road Music: Catching Live Music As You Travel

The Festival Django Reinhardt, held every summer at the Château de Fontainebleau near Paris, is named after the most famous jazz musician Europe has ever produced. By combining the continent’s gypsy or Roma music with American jazz, the late guitarist (and his principal foil, violinist Stéphane Grappelli) created a music so vibrant that interest in it has never flagged. Five of the event’s best musicians have been touring North America this summer as the Django Festival Allstars, and when they appeared at the Montreal Jazz Festival on June 29, they joked from the stage that it was a treat to finally talk in French again. The quintet played superbly—reminding us how versatile a button accordion can be—and bantered playfully with the hometown crowd in their shared language.

Suddenly a young woman cried out in frustration, “Can you speak in English?” Lead guitarist Samson Schmitt started to accommodate her, but the bulk of the audience drowned him out with cries of “Non, non, en français, c’est une ville francophone” (“No, no, in French. This is a French-speaking city”). It was a reminder of the language tensions still alive in the Quebec province and of the ardent pockets of resistance to the English language’s global hegemony. It was also a reminder that listening to music in a different town can be a very different experience from listening to the same act at home. Hearing the Django Festival Allstars in Montreal was more revealing than their shows in the States could have been.

When we hear live music at home, everything is familiar. We know where to park and drink before the show; we know the ins and outs of the venue, and we’re one of the local crowd. When we hear live music while we travel, much is unfamiliar—the logistics can be more of a hassle, but the whole thing is more of an adventure. And the interaction between the performers and the audience can shed new light on the music.

I took a 25-day road trip this summer to see family, friends, museums, national parks, state parks and more, but I organized it to maximize my live-music opportunities. There were challenges, yes, but they were worth it. Our first stop was Syracuse, New York, where my son lives. The second night there, Thursday, June 27, he and I attended the Syracuse Jazz Festival, a free event in a concrete downtown plaza. Sitting in our camp chairs in a rare patch of shade, we heard a terrific lineup: pianist Bill O’Connell with a band of Latin-jazz stars (trombonist Conrad Herwig, saxophonist Don Braden and bassist Luque Curtis); trad-jazz singer Catherine Russell and the rockabilly-blues guitarist McKinley James (with his dad on drums).

The headliner was the Mavericks, not a jazz band by any definition, but one of the best live acts around. Cuban-American singer Raul Malo deserves the comparisons to Roy Orbison and Elvis Presley, and he has broadened his vision of Latin-country to include Tex-Mex accordionist Percy Cardona and a three-man Caribbean horn section. The nine musicians lent a big-band swing to the group’s old hits and had everyone from grandparents to grandkids dancing in the aisles. The next night, Willie Nelson’s Outlaw Music Festival came to Syracuse’s Empower Amphitheater overlooking Onondaga Lake. Nelson was ill and didn’t appear, but the show went on without him. His son Lukas sang his father’s setlist and played a similar acoustic guitar. As my son remarked, “He sounds just like Willie, only without the nuance.” To soften the sting of Willie’s absence, an unannounced Edie Brickell sang six songs with Lukas.

The previous set featured a reorganized Bob Dylan Band. Session legend Jim Keltner replaced Jerry Pentecost on drums, and multi-instrumentalist Donnie Heron was gone after 19 years with the group—and his steel and fiddle fills were sorely missed. Also transformed was the setlist. Much to my disappointment, all the songs from Dylan’s latest album, Rough and Rowdy Ways, were dropped, replaced in part by four unlikely covers: Chuck Berry’s “Little Queenie,” the Fleetwoods’ “Mr. Blue,” Dave Dudley’s “Six Days on the Road” and the Grateful Dead’s “Stella Blue.”

As usual, Dylan barely spoke to the crowd and banned any close-ups on the video screens flanking the stage (what you saw on the screens is what you saw from your seats). Despite it all, the old man sounded great, crooning and wailing as the moment required and even playing some respectable piano solos. The evening’s highlight was a version of “Simple Twist of Fate” with Willie’s longtime harmonica whiz Mickey Raphael blowing a jazzy solo after every refrain.

Even better was the preceding set from Robert Plant and Alison Krauss. Dylan is a great singer despite his limited voice, but Plant and Krauss are great singers with strong, supple voices—and that makes a difference. The singers’ different backgrounds were reflected in the band: two rock ‘n’ rollers (guitarist J.D. McPherson and drummer Jay Bellerose) with three bluegrassers (fiddler Stuart Duncan, bassist Dennis Crouch and Alison’s brother Viktor Krauss on guitar and keys). The 15-song setlist betrayed a similar diversity; three Led Zeppelin numbers, three Everly Brothers tunes and two Allen Toussaint compositions. It all worked wonderfully. Alison sang Sandy Denny’s part on “The Battle of Evermore” and Don Everly’s part on “The Price of Love,” while Plant sang Phil Everly’s harmony. “When the Levee Breaks” featured a long, eerie, twin-fiddle duet by Alison and Duncan. When Alison sang lead on the old British ballad “Matty Groves,” the people sitting two rows in front of me decided it was a good time to talk about their plans for later. I tried to shut out the chatter and focus on the singing, but in this broken world of ours, it’s difficult to disentangle the obnoxious from the sublime.

The next afternoon, Saturday, June 29, we checked into the Hotel Faubourg, a short walk away not only from the 19 stages of the Montreal Jazz Festival but also from dozens of restaurants in both the city’s historic district and its Chinatown. One advantage of such a festival is the chance to see artists in situations other than their usual band gigs. Trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, for example, played a solo set the day before I came and then played an unaccompanied duo set with legendary bassist Dave Holland after I arrived. To hear such an intense conversation without distractions is a rare privilege—especially in a setting as intimate as Gesu, a former church converted into a 300-seat amphitheater.

Trumpeter Keyon Harrold, who straddles the jazz/R&B boundary, played a band gig at Gesu to support his hit-and-miss new album, Foreverland, and then returned to the venue Monday night for an unaccompanied duo show with pianist Jason Moran, perhaps today’s most important jazz musician under the age of 50. Moran pushed Harrold out of his comfort zone into playing that hinted at untapped potential. Even Harrold’s unsteady singing acquired an emotional depth thanks to the piano/trumpet interplay.

The most exciting set of the festival was Moran’s solo show, a tribute to Duke Ellington at Gesu earlier on Monday. The pianist—wearing a white T-shirt, black slacks and a salt-and-pepper goatee—explained that he didn’t do this show often because it was like climbing a mountain each time. But climb it he did, hammering anchors into the cliff with his dense left-hand chords, and reaching for new handholds with his right-hand melodies. At each stage of the ascent, he would swivel around on the piano bench to talk to the audience about where they’d just been and where they were going next.

Two younger female saxophonists also turned in impressive sets. Lakecia Benjamin wore a skin-tight, silver spacesuit with white boots as she prowled the stage, preaching and rapping about American freedom and women in jazz. It was great show-biz, but she backed it up with terrific playing on her alto sax, digging a groove even as she sent notes ricocheting in all directions. A similar excitement is captured on her new live album, Phoenix Reimagined (Live).

Appearing a day earlier in the same Pub Molson Tent (a free stage open to all), Chile’s Melissa Aldana wore a black jacket over a black-and-white abstract-print dress. Playing material from her impressive new album, Echoes of the Inner Prophet, the tenor saxophonist displayed the muscular tone and harmonic nimbleness of a Sonny Rollins or Joe Lovano, employing honks and squeals not as ends in themselves but as means to achieve an emotional climax, whether soloing over an uptempo rumble or a balladic simmer.

Joshua Redman’s recent album with vocalist Gabrielle Cavassa, Where We Are, came across as a bit tentative and under-rehearsed. But the months since its release have made the co-leaders much more comfortable with each other, and in Montreal the vocals flowed effortlessly into the vocals and vice versa. Mixing pop songs associated with Bruce Springsteen, the Eagles and Glen Campbell with jazz standards from Count Basie and John Coltrane, Redman and Cavassa easily bridged a gap that has swallowed so many others. Because he was in Montreal, Redman encored with “Place St. Henri,” a tune by the city’s native son: jazz pianist Oscar Peterson. It was the first time Redman had ever played the piece in public, but he gave the uptempo bop the exuberance of a new discovery. It was a revelation that couldn’t have happened in any other city.

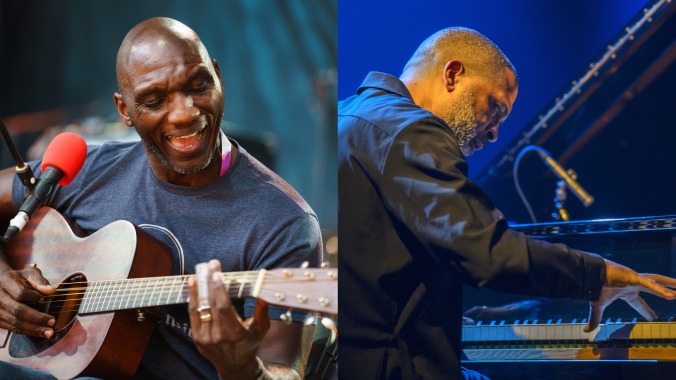

Another free stage, Scene Rogers, was dedicated to blues performers, and on Sunday Cedric Burnside delivered two impressive sets. Each one began with three solo-acoustic numbers with the tall, bald-domed young man in the gray T-shirt sitting in a folding chair and needing no accompaniment to demonstrate the power of the Mississippi Hill Country Blues. Even when he strapped on an electric guitar and called out his drummer and bassist, Burnside’s baritone proved how vital that perpetually threatened genre can still be. The next morning, back at the Hotel Faubourg, Burnside happened to sit down next to us in the breakfast room. He was eager to talk about his grandfather, the legendary bluesman R.L Burnside, and about how his own start as a drummer prepared him to become a bandleader himself. It was the kind of chance encounter more likely when traveling than when at home. He would never have popped up in my Baltimore dining room.

By Wednesday, July 3, we were in Toronto, and I celebrated the Fourth of July in Canada by going to see the Elvis Costello/Daryl Hall Tour as it stopped at the Budweiser Stage on a peninsula jutting out into Lake Ontario. The hipster-intellectual Costello and the mass-marketing genius Hall might seem an odd couple, but they share an abiding faith in pop craftsmanship, a quality exemplified in different ways during their two sets. Costello went on first. Two of the original Attractions—keyboardist Steve Nieve and drummer Pete Thomas—are still with him, as is his longtime bassist Davey Faragher. Guitarist Charlie Sexton left Dylan’s band to join Costello’s, and the two guitarists built the cinematic tension with dueling licks on “Watching the Detectives.”

Wearing a pair of shiny silver shoes and a gray fedora with a black feather, the singer was in a jaunty mood, pulling songs from all phases of his career, including co-writes with Allen Toussaint and Paul McCartney and a preview of his new stage musical coming to London. The highlights were “Everyday I Write the Book,” with the singer turning his earworm hook into a compelling confession, and “(What’s So Funny ‘Bout) Peace, Love and Understanding,” which the quintet charged through like a conquering army.

Hall may not be as ambitious a lyricist or conceptualist as Costello, but he’s a better singer and melodicist. Though he’s feuding with his longtime partner John Oates, Hall did not shy away from the duo’s irresistible hits. Though repetition may have dulled their charms, open ears can’t help but rediscover how impeccably crafted songs such as “Sara Smile,” “Rich Girl” and “Kiss on My List” are. And when Hall sang his exhilarating composition “Everytime You Go Away,” he proved how much better a singer he is than Paul Young, who had the global hit with it.

It was a great evening, but as too often happens at large, outdoor concerts, selfish jerks did their best to spoil it. Most annoying was a woman who stood up to dance, blocking the view of a dozen people behind her. The young usher pleaded with her to sit down, but she insisted her freedom to move was more important than everyone else’s freedom to see. Only when an older usher came down and whispered a threat did she finally sit down. As the usher walked back up the aisle, everyone behind the woman applauded.

The next stage of my trip took me through Michigan. It was a week of great food, waterfalls, sand dunes, boat rides, visionary architecture and sunsets, but it didn’t involve live music, so we’ll skip to Sunday, July 14, in Madison, Wisconsin, when the Fete de Marquette was held in the city’s McPike Park. This annual, free event leans heavily on Louisiana music, including New Orleans’ Soul Express Brass Band and second-line pianist Marcia Ball playing with the Wisconsin horn band, the Jimmys.

But the highlight was Cedric Watson & Bijou Creole. Watson grew up in the French-speaking Creole communities in East Texas, and made a name for himself in Lafayette, Louisiana, as co-founder of the Pine Leaf Boys and later leader of Bijou Creole. His musical partner was often Chris Stafford, the multi-instrumentalist who founded the Cajun band Feufollet. On May 2, Stafford died at age 36 in a Lafayette car crash, and a big photo of him was propped up on the Fete de Marquette stage. Watson delivered a moving eulogy for his friend, and this seemed to give the quintet an extra edge as they brought to life the old Creole sound that fueled both zydeco and Cajun music. Whether playing fiddle or button accordion, the short, goateed leader in the broad-brim, yellow-straw hat turned up the flame on the two-steps, blues and waltzes. When he segued into the traditional “Mardi Gras Song” late in the set, singing it in Creole French, he reinforced the notion that language and locality are crucial factors in music making—and worth traveling to encounter.

My last live-music event on the trip was on Friday, July 19, at FitzGerald’s Night Club, the legendary Chicago showcase for American roots music. Four of us drove from North Chicago’s Wrigley Field (where the Arizona Diamondbacks had defeated the Chicago Cubs 5-2) to the western suburb of Berwyn. We found a table in the large patio behind the 100-year-old brick building, and soon the Kevin Gordon Trio was setting up on the club’s back porch. Gordon, who was born and raised in the Jerry Lee Lewis region of North Louisiana, attended the Iowa Writers Seminar and has lived in Nashville for most of his adult life. He somehow combines those influences of rockabilly, poetry and country craftsmanship into some of the best songwriting of this century. Backed by drummer Aaron “Mort” Mortensen and bassist Ron Eoff, Gordon managed to grab the attention of a summer-evening, outdoor crowd of grandparents, parents and kids with his pulsing rock ‘n’ roll and focused storytelling.

With his sunglasses, gray-plaid shirt and jeans, he looked the part of the twang poet. He sang about cars such as a Buick Elektra and a Pontiac GTO. He sang about a middle-school marching band running into a Ku Klux Klan rally in 1970s Louisiana. He sang about the way the languid bayous of the Gulf Coast can sometimes shine “Like a Saint on a Chain.” Most gratifyingly, he sang “Simple Things,” the first single off his first album in nine years, due in September. That’s something to look forward to. The next morning we climbed into a 2010 Camry and drove the 15 hours (including meal stops) from Chicago to Baltimore. We were glad to be home. We were glad to have made the trip.

Related

Turkish Airlines and Qatar Airways Suspend Mogadishu Flights Following US…

Home » Airlines News of Qatar » Turkish Airlines and Qatar Airways Suspend Mogadishu Flights Following US Embassy Terror Alert, Raising Security Concerns at

Local tourism destinations grow fast

Men sit at the Doha Corniche backdropped by high buildings in Doha on March 3, 2025. Photo by KARIM JAAFAR / AFP DOHA: Local tourism destinations are g

Hajj, Umrah service: Qatar Airways introduces off-airport check-in for pilgrims

Image credit: Supplied Qatar Airways has introduced an off-airport check-in

IAG, Qatar Airways, Riyadh Air, Turkish Airlines, Lufthansa & more…

Turkish Airlines – a Corporate Partner of the FTE Digital, Innovation & Startup Hub – is charting a course to rank among the top 3 global airlines for