New Survey, Old Story: Women Education Leaders Told To Put Jobs Over Family

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When Mellow Lee’s son was in kindergarten, several of his classmates shared that they’d soon become big brothers and sisters. Eager to get in on the excitement, he blurted out that his mom, a principal, was also expecting a baby.

Only she wasn’t.

But before the day was over, that innocent mistake reached the ears of Lee’s supervisor in her West Virginia district. Lee had just taken on the challenge of consolidating two struggling schools serving high-need students, and her boss was less than congratulatory.

“She told me there was no way that I could handle those expectations if I had a baby,” Lee remembered. After that encounter, she never considered having another child for fear she would be overlooked for promotions. “It is a regret I carry,” she acknowledged.

Sixteen years later, Lee is a deputy superintendent in Beaufort, South Carolina, and jokes with her now-22-year-old son that it’s his fault he’s an only child. But her story demonstrates what many women give up to advance in the education sector. In a new survey, three-fourths of women superintendents and other top female district and state leaders said they make sacrifices that men in the same jobs don’t have to endure.

Julia Rafal-Baer, founder and CEO of Women Leading Ed, which conducted the survey, called the results “a reality check.”

“Across the country, women are shaping the future of America’s schools. They’re making high-stakes decisions, driving results and shaping the future for tens of millions of students,” she said. But the survey, from leaders in 37 states, shows women are “second-guessed more, scrutinized for their style instead of their strategy, and expected to ‘overcome’ being women.”

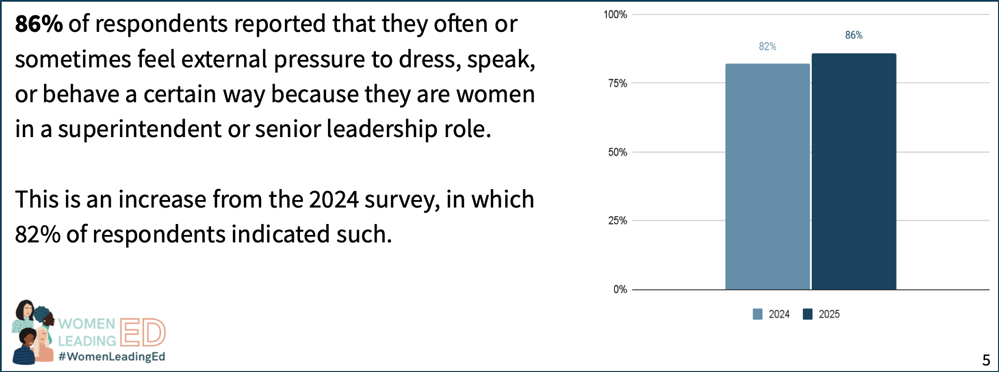

The results, shared exclusively with The 74, also show that 86% of respondents feel expectations to dress, speak or behave a certain way because they are women in senior leadership positions — a 4 percentage point increase over last year.

“No one will take you seriously with a ponytail. No one will take you seriously if you aren’t wearing a suit,” Candace Standberry-Robertson, executive director of system-wide programming for NOLA Public Schools in New Orleans, wrote. Sometimes casual attire is more appropriate for the tasks that come with her position, she said. “Who wants to be all dolled up and sweaty while delivering boxes of instructional materials to schools?”

Others said they’ve faced questions from hiring managers or school board members about balancing work and family life. One superintendent wrote that when interviewing for the top post in a small district, the school board president asked her: “How can you manage being a mom while being a campus leader? We have never hired a lady before.”

And sometimes they don’t, regardless of qualifications.

Over half of respondents said they’ve been passed over for leadership positions that later went to men, and over 70% of the women surveyed reported feeling pressure to earn a doctoral degree in order to be considered for a leadership position. National figures show 45% of superintendents have a doctorate, with women more likely than men to earn the advanced degree.

“Female superintendent candidates won’t apply until they know they’re 110% ready, and male superintendent candidates apply when they’re like 55% ready,” said David Schuler, executive director of AASA, the School Superintendents Association. There’s been progress in districts hiring more women over the past 20 years, but he added, “We need more female superintendents, hands down.”

Not a ‘great look’

Data shows that about 30% of superintendents in the top 500 districts are women, even though women make up nearly 80% of the teacher workforce — an imbalance that some leaders say robs young educators of strong role models.

“The people actually doing the work are women, and the people telling them what to do are men,” said Julia Drake, an assistant superintendent in the Katonah-Lewisboro School District, north of New York City. “I don’t think that’s a great look.”

Before Rafal-Baer founded Women Leading Ed in 2021, Drake attempted to figure out why bias against women was so pervasive in the field. She grew intrigued by the topic as a young principal in New York City. When her assistant principal went on maternity leave, Drake recalled, her male supervisor commented, “Don’t expect her to come back as productive as she was when she left.”

She focused her dissertation on the issue, compiling a sample of over 500 female leaders from 41 states.

One top finding was that people viewed ambitious women in education as “bossy,” but ambitious men as strong-minded. Respondents also felt that staff members were less comfortable being supervised by women.

“I think women are very capable, but also very empathetic and can really bring people together,” she said. “What is sometimes seen as weaknesses is actually a leadership asset.”

Suits, heels, makeup

Examining this year’s data, Emily Hartnett, executive director of Women Leading Ed, pointed to differences in results by age. Leaders under 50 are more likely to say they delayed having children for the sake of their career. They also feel more pressure to conform to a certain image — 93% compared with 78% of leaders over 50.

“I once had a supervisor encourage me to get my nails done,” one woman wrote.

Several said they are expected to wear suits, heels and makeup, even when male counterparts wore golf shirts and sneakers to work.

“When I first started wearing my natural hair, I was told by a mentor that I should reconsider because where I was interviewing to be a principal may not accept ‘that much of my ethnicity,’ ” one district official said. “Of course, I wore my new afro to every interview.”

In response to a new question this year, more than half of the superintendent respondents said board members often second-guess their expertise or undercut their decisions.

One particular example sticks with Dana Arreola, who became superintendent of the Bessemer, Alabama, schools in 2023. The district was about to undertake an $8 million capital improvement project, with new roofs, paint and lighting at several schools. In advance of a presentation to the school board, she reviewed the bid process, fully vetted the architects and conducted a deep dive on facility needs.

But that wasn’t good enough. The members first wanted to hear from a state education official, who happened to be a man.

“My male counterpart ultimately did a great job of reaffirming the information I had already presented,” she said.

A year later, a few board members sent messages to say they initially underestimated her and that her hard work was paying off.

“I began to question my own confidence,” Arreola said. “Receiving notes from my board members felt incredibly validating.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Related

A top recruiter says sports marketing roles are hot right…

Jobs are opening up in the sports industry as teams expand and money flows into the industry.Excel Search &

Public employees and the private job market: Where will fired…

Fired federal workers are looking at what their futures hold. One question that's come up: Can they find similar salaries and benefits in the private sector?

Mortgage and refinance rates today, March 8, 2025: Rates fall…

After two days of increases, mortgage rates are back down again today. According to Zillow, the average 30-year fixed rate has decreased by four basis points t

U.S. economy adds jobs as federal layoffs and rising unemployment…

Julia Coronado: I think it's too early to say that the U.S. is heading to a recession. Certainly, we have seen the U.S. just continue t