He ‘would have won majors’

Lewis Chitengwa would have turned 50 on Jan. 25. I can’t picture him as a 50-year-old. In my mind he’ll forever be a humble and kind young man, and an incredibly talented golfer, one of a handful of extraordinary players who emerged in the early 1990s.

I knew Lewis for a little more than eight years, and they were really good years, until the summer of 2001 when, at age 26, he died during the Edmonton Open on the Canadian Tour.

In 1992, I was coaching the golf team at the University of Virginia and doing my best to bring the world’s greatest players to Charlottesville. Like every other coach in the country, I’d been pursuing Tiger Woods, the best junior golfer in history. It was widely known that he was a good student who announced in eighth grade that he would go to Stanford. But man, he was so good I had to at least try to get him interested in Virginia.

I watched Tiger play eight full rounds of golf in the summer of 1992 and began writing to him on Sept. 1, the date the NCAA designated as the first day a coach could correspond with a high school junior.

The kid was phenomenal. Of the eight rounds I witnessed, he had no bogeys in four of them, including a 66 in the second round of the U.S. Amateur at Muirfield Village, a masterpiece of four birdies, one eagle and 13 tap-in pars.

At Pinehurst No. 7, I saw Tiger dominate the 72-hole Insurance Youth Golf Classic and win by nine shots. The third round there was brutal, with constant rain and wind that pushed the average score to around 77. But Tiger, in an amazing display of focus and concentration, was in the middle of every fairway, hit every green in regulation, and shot 69 with 15 pars and three birdies to build an insurmountable lead.

That summer, Tiger also won four American Junior Golf Association titles and the U.S. Junior for the second year in a row, so when it came time for the Orange Bowl Junior at the end of December, it was a foregone conclusion as to who would win. The only real question was who would finish second.

But on Dec. 30, the day Tiger turned 17 years old, it was Lewis Chitengwa blowing out the candles on the 1992 season.

Lewis upstaged Tiger by beating him at Biltmore Golf Course in Coral Gables, Florida. Lewis, Tiger and Gilberto Morales of Venezuela entered the final round tied for the lead, but only Lewis was able to shoot even-par 71 in the final round to finish at 2-under 282, three strokes better than Tiger, who beat Spain’s Oscar Sanchez in a playoff for second place. Morales dropped to fourth.

Many had heard of Morales and Sanchez, but who was this unheralded Lewis Chitengwa from Zimbabwe? With a little research, coaches soon discovered that his Orange Bowl Junior victory was no fluke. He’d already won the Zimbabwe Men’s Amateur, and was being highly recommended by renowned instructors Wally Armstrong and David Leadbetter.

It wasn’t easy to track Lewis down. No one had cell phones or email back then, and the Chitengwas didn’t have a land line at their home in Zimbabwe. It took more than a month before we were able to establish regular contact – a weekly phone call to a family friend’s office in Harare, the nation’s capital, every Thursday at 11 a.m. “Zim time” (4 a.m. in Virginia).

We’d established a good rapport by March 1993 when in one of our calls Lewis informed me he’d just won the Zimbabwe Amateur for the second year in a row, this time by seven shots. After a good bit of time talking about his latest victory, I asked: “So what’s next on the schedule? You got anything coming up in the next couple of weeks?”

The excited banter with which Lewis had been describing his second Zim Amateur win turned serious. His tone changed, as if he was sharing an important secret, and there was determination in his voice.

“I am going to South Africa,” he said.

I knew enough about South Africa to know that it was still operating under the segregationist system of apartheid – not just unfriendly to Black people but downright oppressive. The country reeked of institutional racism, resettlement camps with miserable conditions that millions of blacks were forced into and treated like cattle. South Africa was a pariah, shunned and boycotted by democratic nations, and it was only slowly, grudgingly beginning to change.

The world’s most inspiring political prisoner, Nelson Mandela, had finally been released after 27 years confined to a cell, but real change in the racist apartheid system of government, including free elections, had yet to occur.

My words came slowly as thoughts turned from golf to basic safety.

“Lewis, why are you going to South Africa?” I asked.

“I am going to play in their national championship,” he said.

Another pause.

“Lewis, what do you think the South Africans will say when a skinny black kid from Zimbabwe comes in and wins their national championship?”

Lewis actually laughed before replying with his customary humility.

“Oh, Coach Moraghan, you know this is a very difficult tournament – 72 holes of stroke play just to make match play,” he said. “Thirty-two will qualify and then it’s two matches each day with a 36-hole final. And many good players. A very, very strong field. I will do well just to make match play.”

It was about two years after that conversation that Lewis, then a first-year collegian at Virginia, was given an assignment in English 101 to write an essay about the greatest day in his life.

There was the necessary preamble before Lewis could get to his “greatest day.” He described his arrival at the East London Golf Club – on the South African coast about 300 miles south of Durban – and being told by a guard that he couldn’t enter the clubhouse. Assuming the Black kid couldn’t possibly be a tournament player, the guard told him, “Caddies can’t come in here, you go around back.”

He described the 45 mph wind gusts that plagued the third and fourth rounds of stroke play, and how he’d battled to earn a spot in the match-play bracket. He described each of his first four matches, including a 5-and-3 drubbing of future PGA Tour pro Rory Sabbatini in the semifinals.

“Rory had done extremely well to reach the semifinals,” Lewis wrote. “He had a steady round and finished 3-under par, but it wasn’t enough to beat my eight birdies in 15 holes. I had reached the finals!”

And then, writing about what would become the greatest day in his life, he described the scene at the start of the 36-hole championship match.

“Approximately four-hundred people packed the first tee box. Among the large gallery were a group of black maids who had left their dirty laundry and dishes to watch me in the finals. This was a rare sight for black women in South Africa.”

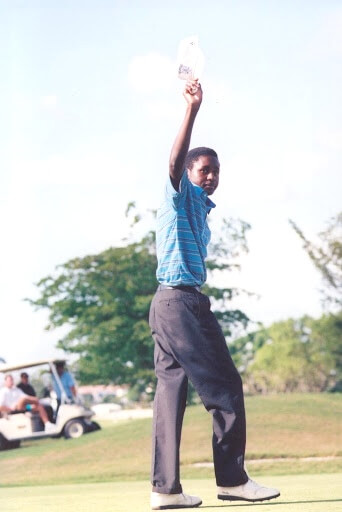

Over the course of that week, Lewis had become an inspiration, a hero to every black caddie and domestic worker and to thousands beyond the club as word spread of this extraordinary young man doing the unthinkable. When he closed out his opponent, Hugo Lombard, on the 34th hole to win, 4 and 2, his gallery of black caddies and maids rushed the green in celebration. Shouting, singing, dancing and crying, they quite literally carried him off the golf course: “Lifting me up on their shoulders, and chanting in their native language!” he wrote.

“The president of the South African Golf Federation announced Lewis Chitengwa as the South African Amateur champion and his wife presented me the trophy,” his essay concluded. “This was an emotional moment. Lifting that trophy was such a great feeling of accomplishment and personal satisfaction.

“Becoming the first black to ever win this significant national championship was the greatest day of my life and a dream come true.”

In the eight years that followed Lewis’ historic victory in South Africa, he continued to enjoy great success. He won the Zimbabwe Amateur a third time, was named ACC Freshman of the Year and became a two-time All-American at Virginia. He won two college tournaments, tied for first in another and finished seventh in the NCAA Championship, which was then the best finish by a Cavalier golfer in more than 50 years.

There always seemed to be some mad scramble involving passports, textbooks or Titleists, and whether Lewis was winning a long drive contest or battling through final exams with little sleep, he always seemed to be smiling. Well, at least that’s how I remember it now.

We had some extraordinary adventures together on and off the golf course. In Puerto Rico, where he made six birdies in a row in one of the rounds, Lewis and his teammates hiked through El Yunque rainforest and swam under a waterfall. In Tallahassee, Florida, he beat another future PGA Tour player, N.C. State superstar Tim Clark of South Africa, in a playoff for the individual title.

In the Philippines during the World Amateur, Lewis and I spent four hours in the U.S. Embassy because of a mistake by UVA’s International Office. There was the time we nearly froze to death at Royal Portrush in Northern Ireland, a trip to a hospital in Knoxville, Tennessee, a couple of visits to UVA’s Student Health Office and a lot of great golf, including nine team victories.

There always seemed to be some mad scramble involving passports, textbooks or Titleists, and whether Lewis was winning a long drive contest or battling through final exams with little sleep, he always seemed to be smiling. Well, at least that’s how I remember it now.

After graduating in 1998, Lewis turned pro and was frequently in contention on the Sunshine Tour in Africa, on the Buy.com Tour (what is now the Korn Ferry Tour) and on the Canadian Tour. Lewis also received a couple of exemptions into PGA Tour events, and it appeared to be only a matter of time before he would be out there as a full card-carrying member.

On a number of occasions over those years I would run into Earl Woods, Tiger’s father, who held Lewis in high regard. In one of our conversations, Earl indicated that it had been “a good lesson for Tiger” when Lewis beat him in the Orange Bowl Junior. And Earl would always mention the South African Amateur victory, typically raising a finger for emphasis and saying with what sounded like real authority and pride: “What he did down there, what he did in South Africa, he will always, always be the first.”

And then, suddenly, it all came to a terrible end. In June 2001, after back-to-back top-10 finishes in British Columbia, Lewis was again in the hunt at the Edmonton Open. He followed up an opening round 70 with 67 on Friday before falling ill on Friday evening.

On Saturday, he was rushed to an emergency room where he died that afternoon. Meningococcal meningitis, a deadly bacterial disease that had been lingering in the Edmonton area for close to a year, had killed 26-year-old Lewis Chitengwa.

It was a devastating loss for thousands of people who knew and loved him, as well as a tragedy for golf. Having at one time or another beaten every great player of his generation, Lewis appeared destined for success on the PGA Tour. Fellow Zimbabwean Nick Price, a three-time major winner, and South African Gary Player, who collected a career Grand Slam, both insisted many times in the years that followed that “Lewis would have won majors.”

I still believe that what Lewis did in winning the national championship of apartheid South Africa was, for that part of the world, the equivalent of Jesse Owens winning gold medals in front of Adolf Hitler in the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

Perhaps he might have if he’d gotten the chance. But what he did accomplish in his short life was truly amazing. I still believe that what Lewis did in winning the national championship of apartheid South Africa was, for that part of the world, the equivalent of Jesse Owens winning gold medals in front of Adolf Hitler in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Or Joe Louis knocking out Hitler’s heavyweight, Max Schmeling. Or the African golf equivalent of Jackie Robinson integrating baseball in America.

Yes, I loved Lewis as if he was my own son. For years I struggled to watch the PGA Tour knowing that he would have been – should have been – out there. And I imagine those same thoughts will creep in now when the PGA Tour Champions is on, with Lewis’ contemporaries making their debuts as 50-year-old rookies.

Of course I wish we’d had more time, and wish Lewis had been given more time for more amazing accomplishments, more history-making. But that’s when I remind myself to treasure every moment we had, and to remember him forever.

Mike Moraghan was the men’s golf coach at the University of Virginia from 1989-2004. He has been executive director of the Connecticut State Golf Association since 2011.

Photos Courtesy Mike Moraghan

© 2025 Global Golf Post LLC

Related

5 Things I Never Play Golf Without: David Dusek

Our 11-handicap equipment writer always brings his favorite divot repair tool, a portable speaker and some high-tech gear to the course.As long as the weather i

Donald Trump’s golf course wrecked by pro-Palestine protesters

Pro-Palestinian protesters have vandalized parts of U.S. President Donald Trump's golf course in Scotland in response to his proposal for the reconstruction of

Man holding Palestinian flag scales London’s Big Ben hours after…

CNN — Emergency services were called to London’s Palace of Westminster on Saturday a

EPD: Drunk driver parked car on golf course

EVANSVILLE, Ind. (WFIE) - Evansville police say they arrested a man after finding him drunk in his car that was parked on a golf course.Officers say they were c