Golf courses have a tee time problem. This startup is helping to solve it

A new startup called Noteefy has been helping golfers and golf courses alike with a tee time conundrum.

getty images

At the height of the pandemic, Jake Gordon was like a lot of golfers in the Los Angeles area. A relative newcomer to the game, he could hardly get enough of it. He could also hardly get a tee time.

“I was the designated reservationist in our group,” Gordon says. “So, if you caught me on a Friday, I was that guy constantly refreshing the page for every course in the area, looking for an opening. The pain and suffering was real.”

This was not a new story in L.A., the busiest year-round metropolitan golf market in the country. But it had grown more common since the Covid boom. And crowded tee sheets were not the only issue. The rise of bots and brokers had compounded the problem. Unwanted intermediaries snatched up many bookings almost as soon as they appeared (and often cancelled them last-minute, leaving gaps in the tee sheet that were nearly impossible to fill).

None of this was good for golfers. It wasn’t great for course operators, either.

Clicking and refreshing in his search for tee times, Gordon, a hard-driving twentysomething with a background in technology startups, came to the classic entrepreneur’s conclusion: There had to be a better way. In collaboration with his friend, Dathan Wong, a software engineer and fellow golf fanatic, he put his mind to creating one.

As Gordon saw it, despite booming demand for tee times, capacity wasn’t really the problem; after all, if he waited long enough and searched hard enough, a spot on a tee sheet would usually open up somewhere around the city. The problem was the hassle and the inefficiency, which led courses to lose revenue and golfers to lose their minds.

“The process was way too manual,” Gordon says. “It was also impossible to know real-time inventory at all the different courses. And then on the other side, you had these courses that were getting hundreds of calls that they couldn’t answer and no way to get those golfers on a waiting list to fill those last-minute cancellations.”

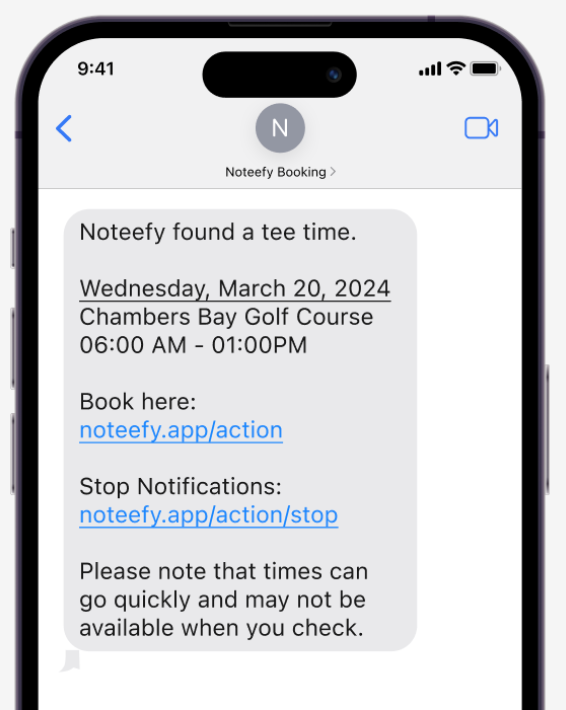

The solution, he determined, was to make access more equitable by building a digital tee time assistant that could match real-time supply and demand. The instant a slot opened, the system would send golfers an automatic alert. And if nothing was available at their target course, the system would clue them in to openings at other nearby properties.

For inspiration, Gordon and Wong looked to Open Table and Resy, which have an alert functions to inform diners of availability, and online travel services like Google Flights and Expedia, which sync up customers with air carrier inventory. By spring of 2022, they were ready to launch. They called their product Noteefy.

Unlike some well-known digital platforms in the golf space, Noteefy (pronounced “notify”) was not developed as a third-party booking service. In fact, Gordon and Wong weren’t going directly after golfers. Their customer was the course operator, who would pay a software licensing fee and share the benefits at no cost to the golfer via a free-to-download app.

“We weren’t looking to tackle this from the consumer side,” Gordon says. “That’s where you get things like bots and brokers who are out to monetize the process against the will of the course. We needed to get buy-in from the suppliers.”

Noteefy

The first supplier to bite, in 2022, was Brian Reed, then the general manager of Simi Hills Golf Course, a busy public facility just outside L.A. As at many area courses, the reservation line at Simi Hills was flooded daily. Keeping up with the calls was tough. Maintaining a list of names and call-back numbers was out of the question.

“So, when Jake called me up out of the blue and said, ‘What if I could build you an automated waiting list?’ I didn’t really have to think about my answer for too long,” Reed says.

Nor did it take long to see a difference. Soon after signing on with Noteefy, Reed noticed fewer empty slots on his tee sheet. Last-minute cancellations were getting filled. At the same time, call volume dropped, as golfers now had a more seamless option than trying to ring the pro shop. The upshot was less hair-pulling for the customer, and more income for the course. By the end of the year, Reed says, Noteefy bookings had accounted for upward of $40,000 in revenue that might otherwise have slipped away.

“We went from capturing almost none of those cancellations to getting at least a few a day,” Reed says. “That might not sound like much. But when your average green fee is $50 to $70, and every day you’re getting more of them, it adds up.”

As word got around, other operators bought in, too. Next up was the golf course management company KemperSports, which installed Noteefy at three of its properties, two in L.A. and one in North Carolina, before adding the software to its national portfolio. The pace of growth accelerated. Over the next 18 months, Noteefy expanded to more than 500 courses around the country, running the gamut from 9-hole rural tracks to high-end destinations such as Destination Kohler and Cabot Citrus Farms to TPC Scottsdale and Sand Valley.

By which point, Gordon and Wong had quit their day jobs.

In Los Angeles, meanwhile, not much had changed. Landing a tee time was still a lot of work, particularly at jam-packed municipal courses. Local golfers grew fed up. This past spring, simmering frustrations reached a boil, which spilled into national stories about bots and brokers and what many saw as the muni system’s failure to deal with them. In March, five golfers went so far as to file a class action suit against the city alleging that “nothing had been done to ensure the book process is fair to all golfers who wish to play.”

The wheels of government can grind slowly, but all that grousing sped things up. In August, under growing public scrutiny, Los Angeles city and county courses began requiring $10 per player non-refundable deposit on all golf reservations. An additional $10 per-player fee was also imposed on no-shows, and cancellations made within 48 hours. Those new policies put a damper on bots and brokers, but local operators weren’t done.

Last month, American Golf, which operates more than 20 courses in Southern California, including 13 L.A. county munis, adopted Noteefy.

As Gordon is keen to point out, the system was never meant to be a bot-squasher. But he says that is a trickle-down effect. “The technology makes inventory accessible to everyone in real time at no cost to golfers,” Gordon says. “In doing that, it makes bots useless because there is no access or information advantage for bad actors.”

Bots or not, Gordon says he expects L.A. county courses to see millions of dollars in incremental revenue, a roughly 30 percent reduction in phone calls and “thousands of happier golfers.”

What kind of impact it is having in the county is too early to say. Rick Crowder, head of revenue management at American Golf for L.A. county courses, says he’ll have a clearer picture in another few months but that he’s optimistic.

“I believe in the technology,” Crowder says.

The licensing fee for Noteefy varies from one operator to the next depending on the number of courses they run and the volume of play. But Gordon says the cost averages out to “the equivalent of one to two tee times per month, and we deliver a few tee times a day.”

And he sees applications in other industries. By Gordon’s calculations, golf courses have been leaving more than $100,000 a year on the table from last-minute cancellations going unfilled. The losses, he says, are just as great or greater elsewhere. Hence his plan to expand Noteefy to other services, such as hotels and spas to help resolves what he believes is a “$1 billion problem” in the high-end hospitality sector.

Muni golf in L.A. might not count as high-end, but it’s hard to put a price on a tee time with your buddies.

“It’s still a grind to get one,” Gordon says. “But our luck is much better now.”

Related

5 Things I Never Play Golf Without: David Dusek

Our 11-handicap equipment writer always brings his favorite divot repair tool, a portable speaker and some high-tech gear to the course.As long as the weather i

Donald Trump’s golf course wrecked by pro-Palestine protesters

Pro-Palestinian protesters have vandalized parts of U.S. President Donald Trump's golf course in Scotland in response to his proposal for the reconstruction of

Man holding Palestinian flag scales London’s Big Ben hours after…

CNN — Emergency services were called to London’s Palace of Westminster on Saturday a

EPD: Drunk driver parked car on golf course

EVANSVILLE, Ind. (WFIE) - Evansville police say they arrested a man after finding him drunk in his car that was parked on a golf course.Officers say they were c