Hong Kong

CNN

—

Perched atop several flights of concrete stairs, Blue Lotus Gallery is nestled beside hipster coffee shops and vintage stores in the narrow, tree-lined lanes of Hong Kong’s artsy Sheung Wan district.

It’s also surrounded by basketball courts: in parks, balanced on rooftops and invisibly sequestered between skyscrapers. All in all, there are 22 courts within a 600-meter (1,968-foot) radius of the gallery.

Its proximity to so many basketball courts is, oddly, not an anomaly in Hong Kong.

American photographer Austin Bell estimates that the city has more outdoor courts than even New York or Los Angeles, after scouring satellite images and as part of his mission to photograph every one of them in Hong Kong. It’s the subject of his exhibition at the gallery, running until February 23, and his photobook, “Shooting Hoops.”

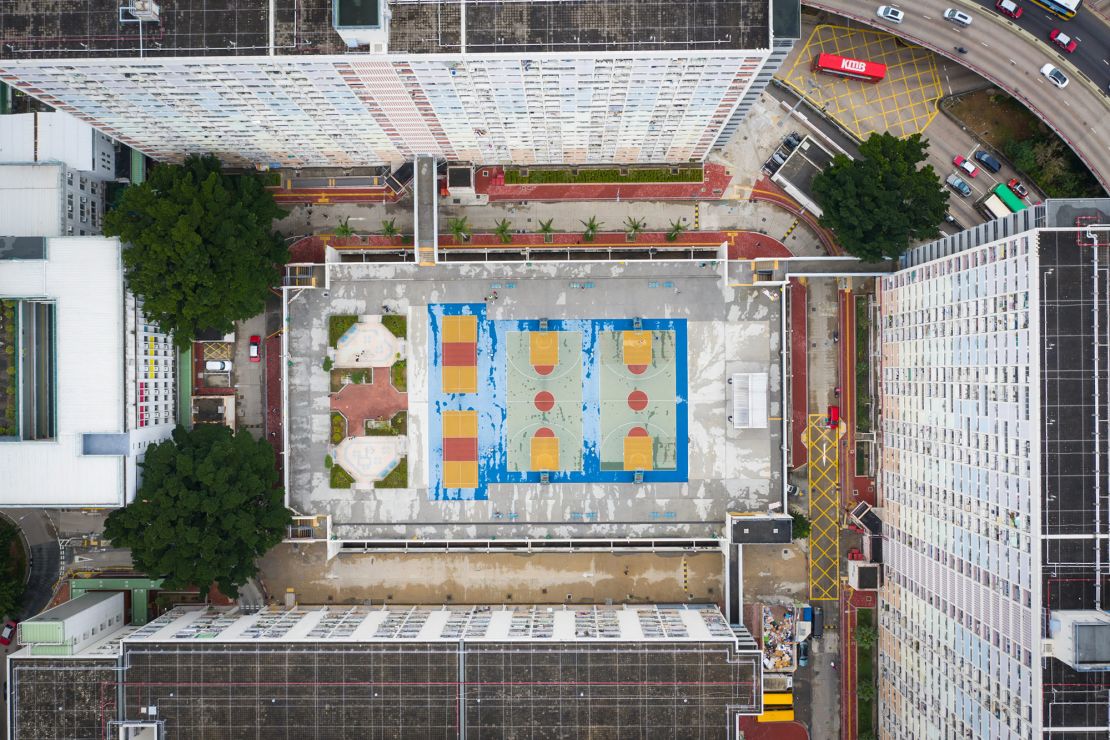

Using his camera and drone, Bell took over 58,000 photos of 2,549 colorful basketball courts; a project spread across three years due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The project was a way to “experience the city” and examine its often unconventional approach to urban design, said Bell. “It’s not really about the sport — it’s more just about the architecture, the color, the surroundings and the topography of Hong Kong,” he added.

Bell’s fascination with Hong Kong’s basketball courts began with his first trip to the city in 2017, when he visited the colorful Choi Hung, a rainbow-colored public housing project with multiple basketball courts in front of its tower blocks, vividly painted marigold yellow, royal blue and emerald green. It’s become one of the city’s “Instagram hotspots,” attracting photographers like Bell to capture its facade.

After taking the photo, he didn’t think much of it — until he started seeing basketball courts in other unusual and colorful locations.

“I started mapping them on Google Maps,” Bell said. “I came back in the fall of 2019 to shoot them, and after two weeks, I said, I need to try and find all of them.”

Poring over satellite images, Bell identified basketball courts hidden among housing blocks, perched on mall rooftops and multi-story parking lots, or shrouded in thick jungle on remote islands, tracking them obsessively in spreadsheets.

When he began the project in earnest, Bell said he photographed up to 100 courts on some days — a number that he said “isn’t that crazy” when considering the density of Hong Kong, which ranks fourth internationally with 7,060 people per square kilometer, according to 2021 data from the World Bank.

On one occasion, he challenged himself to shoot as many courts as possible in a single day, planning a route through many of the city’s most populous residential neighborhoods, like Tuen Mun, Tin Shui Wai and Yuen Long.

“I was just going out to take one diagnostic picture of each court and see how many I could do,” said Bell. The main limitation was the drone batteries, and he anticipated shooting around 200 — but surprised himself once he got home and counted 475.

Not all of the courts were that accessible: some required a full day of traveling, like the remote island of Ap Chau, Hong Kong’s smallest inhabited island that was settled in 1952 by Christian missionaries from Beijing.

People are often absent from Bell’s photos. In part, it’s because he visited the courts in the early morning or late afternoon to avoid the harsh noon sun, but on the other hand, Bell did not want to disturb people on the court.

Over the years, Bell has observed a multitude of uses for the basketball courts, beyond their intended purpose. “I’ve seen choral practices, people walking their pet tortoises, people drying orange peels, everything you could imagine,” he said. “Its main purpose is basketball, and you’ve got big signs saying, no other ball games, no hanging laundry, no remote-control cars or whatever — but you still see all that stuff.”

“It’s so many different things all the time, I think that’s what makes it compelling. But it’s also just the fact that, there’s just not that many other (public) spaces to do things.”

Basketball — a game invented in the US in 1891 as a safe but entertaining non-contact sport for the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) — has been a perennial favorite in Hong Kong for more than a century.

Jeroen van Ameijde, an assistant professor of urban design at The Chinese University of Hong Kong who contributed an essay on the topic to Bell’s photobook, speculated that the arrival of the YMCA in the city in 1901, followed by the construction of the organization’s (at the time) cutting-edge sports facilities, was likely what sparked Hong Kong’s basketball craze.

As the city’s population expanded rapidly in the 1950s and ‘60s, recreational space was a key consideration for city planners. This was later codified in guidelines for new public housing projects, stipulating the need for one outdoor basketball court per 10,000 residents — a higher ratio than any other outdoor sports facility.

“It is much smaller than a football (soccer) pitch, it’s relatively easy to maintain, and in some cases, can be used for dual use,” Van Ameijde told CNN in a phone interview.

While incorporating leisure facilities into urban design is common, Hong Kong’s population-based guidelines are unusual, said Van Ameijde. It’s symptomatic of the city’s high density and scarce land, where maximizing efficiency is vital: for example, the proximity of recreational facilities to residents aims to make housing projects and districts “self-contained,” like a 15-minute city where everything is within walking distance, explained Van Ameijde.

This culture of space efficiency has evolved in recent years into the “beautifying” of some of these leisure spaces, said Van Ameijde, pointing to the work of cross-disciplinary design firm One Bite Design, which has upgraded several rooftop and mall basketball courts with vivid designs.

“The basketball courts always find a way to puzzle into the urban fabric, whether it’s in between buildings, or on rooftops of shopping malls,” said Van Ameijde. “It’s an interesting balance, this sort of hyper-dense mix of both life and work, commerce and efficiency, which is very much in the DNA of Hong Kong.”

Hong Kong’s public basketball courts are just a fraction of the story though, accounting for less than a third of the ones Bell snapped. The majority of Bell’s photos, around 1,800, are of school basketball courts that he captured using a drone.

Accessibility is one of the biggest differences Bell has observed between the basketball courts in Hong Kong and New York — the latter of which he believes has the world’s second-highest number of outdoor courts, and where he’s shot around 1,000 courts so far and has mapped 1,000 more.

“You would never know it’s there unless you were up in a building somewhere looking down on it,” said Bell said of Hong Kong’s school basketball courts. “So I think that was part of the appeal too — I wanted to conquer these walls through the aerial dimension, and get everything that’s hiding behind them.”

Almost all of these images were shot with a drone — something he adds is now not possible, since the tightening of drone laws in Hong Kong in late 2022.

It’s one of the reasons why, even as Bell continues to monitor and track the locations of new courts, he doesn’t think he’ll revisit the project in the future. “The number has already changed. There are already new ones since I finished this project — new housing (projects) have been built, there’s probably some that have been torn down. The number is constantly fluctuating,” he said.

But the exhibition, and the book, is about more than documenting a niche topic: for Bell, his mission to find and photograph every court was an exercise in making the mundane magical.

“We take all these visual things, like basketball courts, for granted,” he said, adding that when, “in reality, when you condense them together in a picture, or put them in 2D, you can see it’s really something different.”