Do New Obesity and Diabetes Drugs Also Curb Drinking, Gambling, and Other Addictions?

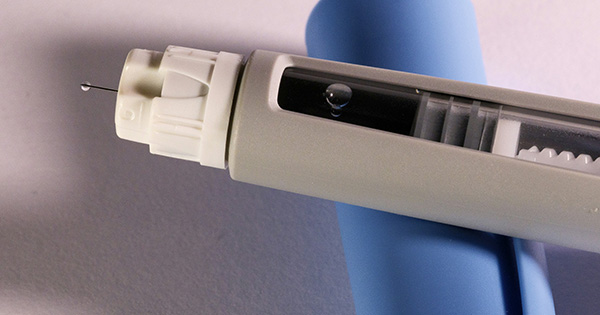

Drugs originally intended to treat diabetes and/or obesity have been proven to reduce weight loss in patients and may help treat heart disease. That’s why 15 million-plus American adults now take pharmaceuticals such as Wegovy and Ozempic, which list for $900 to $1,400 per month. But what if those drugs might also curb appetites for drinking, gambling, or opioids? Or fortify against dementia? What if they might ramp up your sex drive (or alternatively, turn it down)?

All of those possibilities have emerged in mostly small-scale studies of “GLP-1” drugs like Ozmempic and Wegovy. Research out of Sweden and the University of North Carolina suggests weekly doses of the drugs’ active ingredient, semaglutide, correlated with reduced drinking and alcohol-related hospitalization in participants with alcoholism. A Penn State study found decreased opioid cravings in patients with that disorder who took the active ingredient in the GLP-1 drug Saxenda.

On the other hand, one study found an Ozempic-like drug had no effects on Parkinson’s disease, leading some researchers to caution against excessive optimism. And the New York Times recently reported on conflicting sexual research: some small observational studies show obesity drugs can crimp sexual desire, while larger trials show they can raise it. BU Today asked Pietro Cottone, Valentina Sabino, and Ivania Rizo to assess the research. Cottone is an associate professor of pharmacology, physiology, and biophysics, Sabino is a professor of pharmacology, physiology, and biophysics, and Rizo is an assistant professor of medicine at Boston University’s Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. Rizo is also director of obesity medicine at Boston Medical Center, BU’s teaching hospital.

Q&A

With Pietro Cottone, Valentina Sabino, and Ivania Rizo

BU Today: Why might weight-loss drugs also curb addictive behaviors for things like gambling and drinking?

Cottone: GLP-1 is a hormone that stimulates the release of insulin from the pancreatic islets and curbs hunger, among other actions. GLP-1 drugs are a class of medications that mimic the way the GLP-1 hormone works in the body. Obesity is a multifactorial disease, and the inability to limit food intake, especially of high-calorie, palatable foods, is one of the contributing factors. Food intake can be driven by energy mechanisms—eating when we are energy-depleted—but also by eating for the hedonic value of food. Historically, the view of a neat dissociation between the need-related and the reward-related components of obesity has prevailed in the scientific community.

Today, this rigid dichotomy has been dismantled, and increasing evidence shows that many metabolic hormones have a profound impact on the brain reward function. This seems to be the case for GLP-1. The brain reward system plays a critical role in perpetuating behaviors that are important for survival—feeding, reproductive behavior, etc.-—through release of dopamine, responsible for the “pleasure” sensation. GLP-1-mimicking drugs reduce dopamine release in the brain reward system, and reduce the hedonic value of food.

People taking GLP-1–mimicking drugs have started reporting to be less interested in drinking alcohol and taking nicotine products. These drugs may also reduce some types of compulsive behaviors—for example, gambling, nail-biting, and online shopping. Indeed, alcohol, drugs of abuse, and other compulsive behaviors hijack those exact reward circuits in the brain that make us interested in eating tasty food and in reproducing. One hypothesized mechanism is that, when taking alcohol or drugs or engaging in compulsive behaviors, the reward system is flooded with a large amount of dopamine, which drives the repeated use. Researchers have found that drugs mimicking the actions of GLP-1 prevent the release of dopamine in the brain in response to alcohol or cocaine. Drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy may make people feel less pleasure after engaging in compulsive behaviors, so that they then become less interested in pursuing them. Scientists are currently studying what other transmitters and processes these drugs may affect in the brain.

Rizo: Weight-loss medications like GLP-1s don’t just affect hunger and metabolic dysfunction—they influence how the brain processes reward. These drugs act on areas in the brain, like the mesolimbic system, which is involved in feelings of pleasure and motivation. This system plays a role in cravings for food, but also for other rewarding behaviors like drinking alcohol, gambling, or even shopping. So when these medications reduce food cravings, they might also dull the drive for other types of dependence-related behaviors. The medication turns down the “reward” signals in the brain, not just for food, but for other temptations, too. At this time, we only have anecdotal evidence. Multiple, randomized controlled trials have been initiated to determine whether GLP-1 medicines have therapeutic impact on these disorders.

BU Today: Why might those drugs also curb dementia?

Sabino: A recent study found that patients with type 2 diabetes who were prescribed semaglutide had a lower risk of Azheimer’s disease compared to other antidiabetic medications, and that the results held regardless of age, gender, or presence of obesity. At least 40 per cent of all cases of Alzheimer’s are linked to modifiable risk factors. Examples are type 2 diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular factors, alcohol use, smoking, and depression.

Since GLP-1 drugs target all these risk factors, it is possible that semaglutide prevents or delays the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s by improving these factors. Antidiabetic drugs as a class have been on the radar for the treatment of Alzheimer’s and dementia for quite a while, as appropriate insulin-signaling in the brain is essential for learning and memory, and insulin resistance may, therefore, lead to or worsen neurodegeneration.

Different mechanisms have been hypothesized to explain the effects of GLP-1 drugs on neurodegenerative disorders. Neuroinflammation plays a crucial role in neurodegeneration and dementia. The receptors for GLP-1 are present in all the main types of brain cells, and scientists have found GLP-1 drugs to have anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions. Another hypothesis includes the normalization of autophagy, a process important in clearing up the brain from misfolded proteins, which are hypothesized to contribute to the onset and the progression of many neurodegenerative disorders.

Clearly, there are still a number of issues that need to be clarified. Data are still preliminary, and larger trials will be needed to confirm these effects. It will also be important to understand whether the drugs can improve dementia in people who have already been diagnosed, and although current studies seem to suggest a beneficial effect, it appears to be only modest. Another aspect that will need to be sorted out is the importance of the ability of GLP-1 [medications] to reach the brain. Currently approved medications have different abilities to cross the membrane that separates the blood from the brain, and this could be a key factor in their efficacy.

Rizo: Clinical trials have revealed a reduction in cognitive impairment in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with GLP-1. The use of a dulaglutide, a GLP-1, led to a 14 percent reduction in diagnosis of cognitive dysfunction reported in patients with type 2 diabetes in the REWIND trial [funded by Eli Lilly]. Two trials using oral semaglutide, EVOKE and EVOKE Plus, are evaluating the change in dementia rating scales assessed at 104 weeks of use in people aged 55 to 85 years without or with cerebrovascular disease.

GLP-1s work in several ways to protect the brain. They reduce inflammation in the brain, which can damage nerve cells over time and lower oxidative stress, a harmful process that leads to cell damage. They also help prevent the buildup of amyloid plaques and tau tangle, two key markers of Alzheimer’s disease that interfere with normal brain function. These medications have been shown to improve connections between brain cells, called synaptic plasticity, which is important for learning and memory and to support the growth of new brain cells while protecting existing ones from damage.

While early research in animals has been very encouraging, more studies in humans are needed to confirm how well these medications work for people with Alzheimer’s. However, they are generally considered safe, with fewer side effects than some other treatments. This makes them a promising option for future therapies aimed at reducing the risk or slowing the progression of dementia.

BU Today: Science has recently revisited past assumptions, such as the benefits of moderate drinking, based on new evidence. How confident are you in the studies about other effects of weight-loss drugs? What further research must be done?

Cottone: We do believe these drugs may have the potential to be useful in a wide range of addictive disorders. Clinical trials aimed at understanding whether and how these drugs may alter people’s drinking, smoking, and compulsive behaviors are currently underway. Despite the current evidence though, more clinical studies are needed to confirm these observations. We are still at the beginning of this exciting journey, and many questions remain unanswered regarding their efficacy in different subgroups, dosages, treatment durations, and potential rebound effects.

We do believe these drugs may have the potential to be useful in a wide range of addictive disorders.

For example, a central point that will need to be clarified is whether body weight of patients influences the efficacy of the drug in reducing addictive behaviors. It is still unclear whether this class of drugs may be efficacious in reducing addictive behaviors only in those individuals affected by obesity. Although there are no data to support this, a pure speculation may be that obesity may be accompanied by changes in the reward circuitries, which increases sensitivity to the effects of this class of anti-obesity drugs over a wider range of compulsive behaviors.

Rizo: Right now, we have some exciting early data, but it’s mostly from small studies or observations. For example, there are reports that people on these medications drink less alcohol or gamble less, but these findings are often based on personal experiences or small groups of patients. To be truly confident, we need large, long-term clinical trials that specifically look at these effects. Researchers also need to study different groups of people to make sure the benefits apply broadly. So while the early signs are promising, we still have a lot to learn.

BU Today: Curbing all of these cravings, if confirmed, would be beneficial. But are there potential downsides that are physiologically linked to obesity drugs’ positive effects—for example, the reported effects on sexual dysfunction?

Rizo: Yes, there could be. Because these drugs affect how the brain processes reward, there may be a possibility that it also can dull pleasurable experiences. We do not have enough data to state if it is linked to changes in sexual drive. In a study of young healthy men, dulaglutide, a GLP-1, did not decrease sexual desire. A thematic analysis found that some users reported an increase in sexual drive/libido while taking GLP-1s. GLP-1 medications may affect sexual desire, but the effects are complex and vary from person to person. Some people report an increase in libido, while others report a decrease.

Because these drugs affect how the brain processes reward, there may be a possibility that it also can dull pleasurable experiences.

BU Today: Even if the drugs decrease the heart risks of excessive weight, do they convey the positive effects of exercise and healthy diet?

Sabino: Lifestyle changes like exercise or a healthy diet can be difficult to achieve and successfully sustained long-term. Therefore, pharmacological therapy becomes a precious aid for individuals who struggle to lose weight. Still, these drugs do not work independently of a change of habits. These drugs need to be used in combination with healthy eating and exercise, not only because reduced intake is one of the main mechanisms by which the drugs help with weight loss, but also because healthy habits and sustainable lifestyle changes are essential to maintain weight loss once drug treatment is discontinued.

This leads to a very hot question in the field right now: rebound effect. Whether these drugs need to be taken for life or whether they can be safely discontinued without losing all the benefits gained, and if so, how to best transition off are crucial issues, which still need to be fully understood.

Explore Related Topics:

Related

I became a millionaire in my 20s but my sports…

Millions wagered, hundreds of thousands in debt and a pending divorce.Joe C, a native of Chicago, fell into the depths of addictive sports gambling at the age o

Strip executive retiring after 3 decades with gambling giant MGM…

A top executive who oversees multiple properties on the Strip, including one of Las Vegas Boulevard’s most recognizable and successful casino-hotels, is

Danish Government’s Success with Gambling Addiction

Gambling addiction is a growing concern worldwide, with many countries struggling to find effective ways to regulate the industry. Denmark, however, has e

UFC 313 Gambling Preview: Will Magomed Ankalaev end Alex Pereira’s…

Alex Pereira is back! On Saturday, Pereira puts his light heavyweight title on the line against Magomed Ankalaev in the main event of UFC 313. Before that, J