Categorizing robots by performance fitness into the tree of robots – Nature Machine Intelligence

In the following, insights are given on the process isolation procedure by surveying and the metrics definitions, reference benchmark setups and procedures are summarized. Supplementary Section 1 provides a detailed breakdown of the process analysis, and Supplementary Section 2 provides a more detailed instruction on the metric measurement procedures.

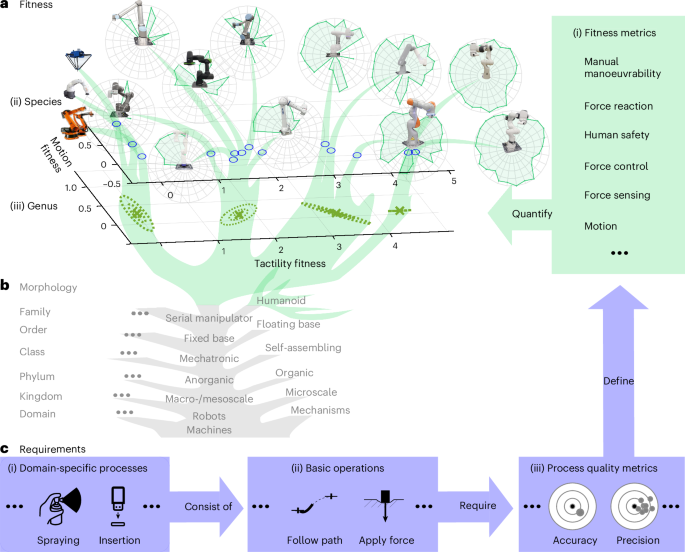

Process isolation by surveying

An extensive literature study, market research and task analysis were conducted to analyse and formalize the industrial manufacturing process. We synthesized reports on industrial robotics use cases reported by the International Federation of Robotics and market analysts like McKinsey & Company, among others. We analysed the standardized industrial process curricula from the German Chamber of Commerce and Trade that are taught at all professional vocational schools to industrial apprentices nationwide. These harmonized curricula provide descriptions of groups of all the relevant single processes such as screwdriving or assembly. Still, even this information is incomplete as it fails to provide single, machine-interpretable basic operations. Thus, to deduce these basic operations, a large set of research use cases from EU Horizon 2020 projects (Extended Data Table 1), trade show demonstrations, factory implementations and expert assessments collected by video analysis of approximately 870 min use-case video footage were analysed. Supplementary Tables 2–10 provide an additional summary of isolated use cases being integrated into the tree of robots website and included in the collection. For the video analysis, we referred to the available videos of trade shows, real use cases or advertised use cases on the official online video platforms of well-known robot and automation system manufacturers, including Kuka AG, Universal Robots and FANUC. We included all applications in our analysis that are (1) in the industrial sector and (2) standard industrial procedures, require human interaction, involve sensitive objects or must be flexibly programmed. For our domain of industrial manufacturing, this structured process led to the main process groups also referred to in the World Robotics Reports43,44 and the German apprenticeship programs of assembly and disassembly, dispensing, welding and soldering, handling and processing44. The list of collected industrial robot processes was clustered (Fig. 2).

Tactile metrics definitions

The following paragraph summarizes reproducible definitions, experimental setups depicted in Fig. 6 and measurement procedures used to obtain the developed tactility fitness metrics from Fig. 2. For each metric group, the reference system for accurately and objectively measuring every metric is first described, followed by the metric definition, and the detailed experiment and evaluation protocol. For detailed graphical measurement procedure descriptions and more detailed information regarding the reference benchmark setups, please refer to Supplementary Section 2. In all the following definitions, force vectors refer to forces in Cartesian x, y and z directions, \(\bar{{{\bf{F}}}}\) is the robot force measurement, Fs is the force measurement measured by an external force–torque sensor (K6D80, ME-Meßsysteme), Fr is the external reference force, Fd,z is the desired commanded force in the z direction, t denotes the measurement duration and N marks the number of experiment repetitions.

All the robot metric results were derived using individual robot systems available at the laboratory and shown in Fig. 4. Only proprietary robot controllers are used and accessible via the standard user interface, if not indicated differently. The test position, ambient temperature conditions of 20 ± 2° and humidity of 40 ± 5%, and other relevant ambient conditions are in line with the EN ISO 9283:1998 standard32. Specifically, the test location is chosen along the central location of the robot reference cube.

Force sensing fitness metrics

We quantify the robot’s internal force sensing fitness in terms of the sensing accuracy, resolution, precision and sensing deviation over time.

Reference systems: all the force sensing metrics are measured using a normalized weight with weight mL of 800 g, which is attached to the robot flange via a steel hook with weight mH of 182 g (Fig. 6a).

Force sensing accuracy, resolution and precision: the force sensing accuracy, resolution and precision quantify the robot’s capability to sense external forces on the end-effector, which is fundamental for all physical interaction. Accuracy compares the actual force with the measured one, whereas resolution describes the measurement fluctuation within one measurement; precision defines the repeatability of the measurement among repeated trials. The experimental procedure is as follows. First, the hook is attached to the robot flange, and mH is compensated for by using the corresponding robot settings. Then, for existing systems, the load mL is fixed to the hook, and after a settling time of 1 s, the external force at the robot’s end-effector is recorded at the maximum frequency that the robot allows (aiming for 1 kHz) and finishes after t = 3 s recording time. The weight is removed, and the robot remains without a load for a minimum of 3 s. This procedure is repeated for N = 30 times to define a statistically relevant precision metric suggested by the ISO 9283:1998 standard32.

Force sensing drift: to ensure reliable task execution in physical contact situations, the robot force sensing quality must be time independent. Thus, we measure the robot force sensing drift to understand the effects of force sensing between that may occur after the typical cycle time of 1 s and (1) a typical task duration of 1 min and (2) a repetition of ten task executions after 10 min, (3) 90 min and (4) one workday (8 h). The robot is first turned off for 6 h to measure the force sensing drift. The hook is attached, and the robot end-effector load mH is set. The robot force measurement is started at a maximum of 10 min after switching on the controller box. Then, the load mL is fixed to the hook. After a set time tset = 1 s, the robot end-effector force recording is started at 1 Hz measurement frequency, which finishes after 8.5 h. The sensing drift metrics are defined in Supplementary Table 14. Although SD1 and SD2 address task-relevant information for a short loading duration of the robot, SD3 and SD4 are concerned with long-term effects of the robot load on the sensed external force. In particular, SD4 measures robot force sensing quality over an entire workday.

Force control fitness metrics

Nine metrics measure the tactile controller fitness: force accuracy, force resolution, force precision, step response force settling time, step response force overshoot, minimum applicable force, impact stability and force control bandwidth against the ground. All the mathematical definitions are listed in Supplementary Table 17.

Reference system: to establish a meaningful reference setup for describing the robot force control quality, we refer to our use-case analysis for the choice of contacting materials. This analysis includes multiple material pairs, such as wood and stainless steel, stainless steel on steel, aluminium/copper, flexible materials like cables or food bags, or even stainless steel with glass. However, the most prominent are use cases in which Duroplast workpieces are handled like printed circuit boards, transport boxes or screen testing. Consequently, we chose a contact material pairing stainless steel with hard plastics for our reference test rig.

The contact force is measured using a K6D80 sensor (ME-Meßsysteme) with a maximum measurement frequency of 300 Hz. The sensor is covered with high-density polyethylene with Hc ≈ 63–67 Shore hardness type D (ShD); the robot end-effector is a stainless steel sphere with Hs ≈ 250 Brinell hardness (HB) with 25-mm radius and total additional weight of ms = 0.2 kg (Fig. 6b, left).

Force control accuracy, resolution and precision: the force control accuracy, resolution and precision describe the robot’s capability to reliably and accurately apply forces to object surfaces. Using the apply force process, a contact with Fd,z = 8 N (ref. 35) is established for 5 s. After contact is made and a settling time of 1 s passes, the sensor measurement starts capturing the applied force for Δt = 3 s. This is repeated for N = 30 times, as suggested by the ISO 9283:1998 standard32, to define a statistically relevant precision metric.

Force settling time and overshoot: the force settling time and overshoot explain the robot’s capability to control the contact force when establishing contact with an object’s surface. The force overshoot metric describes whether a robot can handle certain fragile materials. For overshoot and settling time of the robot applied controller force, the desired force is set via the apply force and move to contact processes (if available) as Fd,z = 8 N applied for t = 20 s. The sphere is placed just above the sensor plate at ds ≈ 0.5 mm. First, the measurement of the force sensor is started. Then, the robot is commanded to establish contact and apply force to keep the contact force for the desired duration of t = 10 s. After the sensor finishes the measurement, the contact can be released again. The procedure is repeated for N = 3 times, as suggested by the ISO 9283:1998 standard32, for position stabilization and overshoot.

Minimum applicable force: to define which minimal forces can be used to establish contact with an object and, thus, how delicately a robot can establish contact with an object that may be fragile, we use the robot apply force capability and search for its most sensitive settings. First, the robot apply force feature is used to contact the sensor plate with Fd,z = 0 N for 5 s. If no contact was successfully established, Fd,z is increased in an increment of ΔFd,z = 0.01 N. This procedure is repeated until the sensor establishes and measures successful contact. After contact is made and a settling time of t = 1 s passes, the sensor measurement starts reading and captures the applied force for Δt = 3 s. Using N = 3 measurements with the final setting for Fd,z, the minimum applicable force is determined via external measurement Fs.

Force controller bandwidth: we apply the force controller bandwidth metric to understand how well the force control can react and adapt to new desired contact forces. We define the force controller bandwidth under contact with a rigid surface. If available, the robot research interfaces are used for this metric to define the system’s frequency response. Initially, the robot is brought into contact with the high-density polyethylene surface of the sensor. Then, the robot’s apply force process is used to produce a sinusoidal force profile with an amplitude of 8 N and the frequency ω starting from 0.5 rad s−1 to 66 rad s−1 increasing by a factor of 0.001. After recording the actual forces, the cut-off frequency is calculated, and the metric is defined.

Material variation consistency and impact stability: these two metrics measure the force control consistency and impact stability over material variation. We consider five different material types that are being contacted by the stainless steel sphere Hs ≈ 250 HB attached to the end-effector (Supplementary Table 19).

For the impact stability measurement, the robot is controlled to contact the material at two different velocities, first with low velocity (\(\dot{x}=50\,{{\rm{mm}}\,{\rm{s}}^{-1}}\)) and then at \(\dot{x}=250\,{{\rm{mm}}\,{\rm{s}}^{-1}}\). The contact velocities are verified using a photo-interrupter (precision light barrier LS 203.1 and speed counter MZ 373, Hentschel) and a 10-mm-thick interrupting structure attached to the robot end-effector. The contact forces are measured via the internal force measurement. First, we check whether the force settles within a 3% error bound around the overall force average within 3 s. Then, if this settled force measured by the robot internal sensing \({\bar{F}}_{{{\rm{z}}}}\) is within ±10% of the desired value, we accept the resulting force for benchmarking. The metric is then split into two parts, where (1) the number of materials for which the contact force settled within the defined boundaries ns,m at 50 mm s–1 and (2) the number of cases in which the contact under dynamic conditions resulted in acceptable forces ns,i are considered. Then, both numbers are compared with the number of experiments (N = 5).

Force reaction fitness metrics

The contact sensitivity is derived as a metric to examine the robot force reactions. Contact detection may have two different goals: (1) preventing secondary hazards by stopping at contacts or (2) detecting objects to be handled. Consequently, both purposes need to be considered. We divide contact sensitivity into two scenarios: (1) robot motion without expected contact at higher velocities (CS) and (2) robot motion in a confined space at low velocity that aims for tactile search of an object (CSt), as defined in Supplementary Table 21.

Reference systems: for both metrics, unconstrained collision scenarios are established using the setup shown in Fig. 6c. It comprises a passive pendulum with adaptable effective masses and the contact stiffness of 70 Shore hardness type A. CS considers collisions with velocities of more than 250 mm s–1, whereas CSt considers collisions at low velocities too. The robot is programmed to move in a straight line towards the pendulum at the desired velocity \({\dot{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{{{\rm{d}}}}\) for both metrics. During the motion, the robot end-effector collides with the pendulum. The effective mass me is modified for different contact situations. We apply the most sensitive safety settings to the desired trajectory and observe whether the robot stopped on contact. Stopping was observed visually by a scale, and up to 10 mm breaking distance behind the collision point was considered successful contact detection. For each contact, this procedure is repeated N = 3 times. Afterwards, the velocity is increased. When all the velocities are tested, the pendulum’s mass is increased until all conditions are examined. The exact setup and testing conditions are listed in Supplementary Table 22. The number of repeatable stops at each velocity–mass pair is determined, where we distinguish between the safe stopping behaviour with higher robot velocities nd and lower robot velocities nd,t. It is then put into relation with the number of total contact situations, namely, different masses (\({N}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}}}\)) and different number of tested robot velocities (\({N}_{\dot{{{\bf{x}}}}}\) and \({N}_{\dot{{{\bf{x}}}},t}\)). The overall contact scenarios with Nc = 35 and Nc,t = 25 are evaluated for each metric.

Manual manoeuvrability fitness metrics

The manual manoeuvrability metrics45 have one additional metric called the manoeuvre effort. They reflect three different phases felt by the user during hand guiding, which are defined as start, acceleration and steady motion. Two setups are required to measure the metrics (Supplementary Table 24).

Reference system: the reference system consists of a three-dimensional linear slider with a K6D40 force–torque sensor (ME-Meßsysteme) integrated via a CompactRio system (National Instruments). The sensor is attached to the top of the z axis of the gantry (Fig. 6d). The robot end-effector is attached to the sensor, and the proprioceptive hand-guiding function is activated. The linear axes guide the robot end-effector along a defined trajectory. During motion, the occurring interaction forces Fs are measured, where we seek to understand the required force magnitude in the direction of motion Fs,x.

Minimum motion force: the minimum motion force corresponds to the acceleration phase of the robot kinaesthetic guidance. First, the static friction of the robot joints is evaluated as a metric. This breakout force is described by force and displacement over time. We first command the gantry to place the sensor in its initial measurement position to measure the minimum motion force. Then, we activate the robot’s proprioceptive guiding function. We attach the robot end-effector to the sensor via an adaptor plate. For robots with redundant kinematic structures, the initial robot configuration is adjusted to the desired value or noted down for the sake of precision between all the measurements. Then, the force and position measurements are started using LabVIEW (v.2020 SP1), and the linear units are controlled to move with \(\ddot{{{\bf{x}}}}=1\,{{\rm{mm}}\,{\mathrm{s}}^{-2}}\) for x = 20 mm in the x direction and back. Once the initial position is reached, the force and position measurements stop. Afterwards, the initial robot configuration is checked, and the process is repeated for N = 10 times.

Guiding force and guiding force deviation: the metrics guiding force and respective guiding force deviation quantify the force profile required from a human operator to guide the robot end-effector at constant speed along the desired path.

First, the robot proprioceptive hand-guiding function is activated using the free guidance feature to determine the guiding force and the guiding force deviation. Then, the sensor is placed in its initial measurement position, and the robot end-effector is attached to the sensor via an adaptor plate (Fig. 6e). Next, the force and position measurements are activated. The linear units are controlled to perform a motion with constant velocity \(\dot{x}=250\,{{\rm{mm}}\,{\mathrm{s}}^{-1}}\) (corresponding to the maximum guiding velocity suggested by the ISO/TS 15066:2016(E) standard39), acceleration \(\ddot{x}=1\,{{\rm{mm}}\,{\mathrm{s}}^{-2}}\) and x = 400 mm along the y axis of the gantry. Then, the trajectory is reversed. When the initial start position of the sensor is reached again, the force recording stops. The configuration is checked and corrected, and the measurement procedure is repeated N = 30 times.

Manoeuvre effort: to quantify the effort required from a human operator to manually set the robot end-effector in motion, this metric measures the energy required to accelerate the robot end-effector from 0 to 250 mm s–1 (as the maximum guiding velocity suggested by the ISO/TS 15066:2016(E) standard39).

Kinaesthetic guidance energy: the kinaesthetic guidance energy metric quantifies the effort required from the human operator to move the robot end-effector from one side of the workspace to the other. It can be applied to workplace ergonomic evaluations.

For the kinaesthetic guidance energy metric, the gantry position shown in Fig. 6d and the same experimental procedure explained for the GF metrics are used. Unlike for the GF metric, we evaluate the entire motion, including the phase in which \(\ddot{x} > 0\,{{\rm{mm}}\,{\mathrm{s}}^{-2}}\).

Human safety fitness metrics

For the human safety fitness metric set, we consider the conformance of the resulting collision forces to the ISO/TS 15066:2016 standard. Here transient and quasi-static contact forces are distinguished. Thus, we receive the metrics conformance to ISO-constrained transient collision force St and ISO-constrained quasi-static clamping force Sq.

To measure the constrained collision forces, we use the Pilz robot measurement system for biomechanical force and pressure measurements, which records the force in the z direction for robot contact for 1,000 ms starting with the initial contact. Using the device, multiple spring stiffness and damping materials can be combined. The applied combinations refer to the ISO/TS 15066:2016 standard39 and are listed in Supplementary Table 28. The achieved number of safe transient contacts ns,t or quasi-static contacts ns,q is then divided by the number of conducted constrained collision tests Nc based on the number of tested body-part representations Nb and robot contact velocities \({N}_{\dot{{{\rm{x}}}}}\). We receive the human safety metrics as a percentage of tests, which resulted in forces complying with the ISO/TS 15066 thresholds (Supplementary Table 27).

Finally, all the results are listed in Extended Data Tables 2–6.

The obtained datasets give the worst-case assumptions for the tactile fitness atlas. The mean and standard deviations are obtained for every absolute numeric metric, excluding obvious outliers. The worst-case assumption is derived by the sum of the mean and standard deviation rounded to one or the next multiple of 5. All means and standard deviations are listed with the corresponding metrics in Extended Data Tables 2, 5 and 6.

Related

Yaslen Clemente Shows Off Leg Day Gains and Shares Her…

Yaslen Clemente isn't just an influencer—she's a fitness powerhouse. The social media star is known for her intense workouts, and she recently sha

Samantha Espineira Stuns in Blue Swimsuit and Shares Her 5…

Samantha Espineira knows how to turn heads, both on and off the runway. The successful model and Instagram influencer regularly shares breathtaking

The Best Fitness Trackers To Help You Reach Any Health…

Best Health Tracker: Oura Ring 3Why We Love It: I’ve tried many, many fitness trackers—but I tend not to stick with one watch or band for very long. I’ve

#CycleSyncing debunked: Popular TikTok trend not backed by science

A new study has debunked a popular TikTok wellness trend called cycle syncing, which claims that tailoring a workout routine to match the hormonal changes that